https://tomkinstimes.com/2016/10/kloppocolypse-now-a-detailed-assessment-of-klopps-first-year/

PART ONE

The fact that so many people expected Jürgen Klopp to arrive with a bagful of miracles has possibly undermined the achievements of the charismatic German in his first full year at the club. Anyone describing it as mediocre or underwhelming is clearly not paying attention.

Arrivals partway through a season are always more complicated than those appointed in the summer, although there are some managers who can make a short-term impact by changing little except the mood of the place. In stark contrast with some managers – those who merely offer an arm around the shoulder and say three words as their detailed tactical prep (“four, four, two”) – Klopp has a philosophy, and a well-known one too. He may motivate, but he’s not simply a motivator.

Of course, he could also have made a short-term impact by being a larger-than-life über-star and doing little more, had he chosen that more simplistic approach: keep doing what you’re doing for now lads, only with added confidence, and all will be well. But instead he tried to impose his new ideas – too soon, according to Frank de Boer, who put Liverpool’s subsequent injury crisis down to pushing too hard too fast (although de Boer’s start to life at Inter Milan, with just three wins from nine games and a mid-table position, perhaps shows that it’s never quite that simple).

Klopp delayed instant gratification – the possibility of a few nice early wins playing the Brendan Rodgers way, with no real new instructions – and immediately implemented his own style, perhaps knowing that it therefore meant more teething problems. It’s tough to switch to a hard-pressing style from a more passive approach, and even harder when the fitness regime hadn’t prepared the players for that kind of game over the summer. Results were a mixed bag, and injuries mounted up.

But of course, Klopp – one of the few managers left who plays the long-term game (in a sport where the short-term game is often the only one anyone has the patience for) – showed that he hadn’t done seven years at Mainz and seven years at Dortmund – both with slow-burning starts – because he cared about a few quick, satisfying results at the expense of the bigger picture. Like any manager he’d clearly rather win while his team is in transition – no one wants the pressure that comes with defeats – but either way,this team was going to be put into transition. Rather than trying to find workarounds to the team’s heart condition – taking it easy, being gentle, pussyfooting around – he performed a transplant, and all the pain that brings in recovery.

There were no new signings last season, and yet there were still a ton of changes – to fitness, to tactics and to the personnel plucked from the deeper reaches of the squad. He didn’t feel the need to protect his own ego by being an instant smash, and he must have known that the gain of getting players fitter would only first come with the pain of falling short.

So results were patchy, as players picked up muscle strains, and as the insane schedule left little option to play the kids and the reserves in some cup and Premier League matches.

No one was rushed back to fitness; again, Klopp plays the long-game. Want to throw Daniel Sturridge back early to grab a result? – no. (It’s understandable why Brendan Rodgers felt the need, but not only has Klopp made no exceptions for Sturridge, the player himself is no longer the only goal option, and is now simply part of a goalscoring squad.) Anyone who doesn’t train in the build-up to a game doesn’t play. No player is therefore deemed bigger than the team. Want to play in your favourite position? No – you’ll play where the team needs you, and so that it’s not a singling out on all these issues, everyone else will do the same. Don’t like it? Tough, there are 25 other guys here, plus the kids – and still some money in the kitty.

When people compared Klopp’s start to Rodgers’ entire tenure – the win rates, etc. – I felt there were issues that were being missed out on; such as just 40% of Rodgers’ games coming without “adequate” preparation time (the handicap of just two, three or four days beforehand), whereas Klopp had awhopping 80% of games last season falling within this gruelling schedule. While managers have to deal with seasons that include a greater number of games than the norm of 45-50 (if it includes even a half-decent cup run), the challenges are tougher if he’s thrown into a 63-game campaign, especially if not given the chance to mould the squad himself.

Analysing the First Year

When I assessed how his first eight months had gone at the end of 2015/16, in a detailed piece that took into account the quality of XIs Klopp fielded and the difficulty of fixtures (based on quality of opponent, whether played home or away, and also how many days earlier the previous game had been), I looked at which players Klopp seemed to rate, and who suited his system.

In that piece from May I noted that there were 13 players who Klopp turned to most often – the most frequently selected, but also those he seemed to try and squeeze into his “best” XI whenever possible (although obviously not all would fit at once). This varied, depending on form, of course – and as he himself tried to work out which players he could trust – so there were times when Divock Origi was ahead of Daniel Sturridge, but the sense I got was that both were very highly valued.

(As an aside here, while I don’t take everything a manager says to the media at face value, it’s important to try and read a situation; so when Klopp said that Sturridge was an even better footballer than he’d thought – he was not just an elite finisher – it seemed to me like an honest assessment rather than just talking the player up. I don’t recall Klopp’s praise being as effusive about Christian Benteke, for example, even if he noted his qualities. He didn’t want to keep Benteke because he didn’t suit his style of play, but his words suggested he would love to work with Sturridge, but only if he was fit.)

I called the ones who often made Klopp’s XI his “100%” players. That doesn’t mean that they are 100% perfect, but they would be in his 100%-strength XIs based on the players at his disposal. (Again, in an ideal world he may have some different players, but this is what he has chosen to work with, within the circumstances he faces.)

What’s interesting is that all 13 players are still at the club, although Mamadou Sakho came close to leaving – but of course, that was due to several complicated issues rather than on-field performances. (Klopp clearly liked the player – at least until the events of the tail-end of last season and the summer.)

Due to his late return from Euro 2016, and subsequent injuries, Emre Can has yet to start a league game in 2016/17, but you still sense that Klopp wholeheartedly believes in him, and rightly so; but that he won’t change a successful team on a whim. This season, Klopp doesn’t have to field the midfield compromises (to him) of Joe Allen and Lucas Leiva (now mostly a centre-back, it seems), and even Can only gets a look-in as a squad player right now.

Indeed, even James Milner doesn’t have to compete in an area of the field where Jordan Henderson, Gini Wijnaldum and Adam Lallana have become first-choices; all as part of moving several quality attacking players one row back within the team structure. That said, when Can does play, he won’t be “weakening” the team; he’ll just be a different kind of player to whomever he replaces. So he’s still “100%” in my eyes.

But are all of the 13 players I mentioned from 2015/16 still “100%” ? Well, no. Last season Alberto Moreno was without doubt Klopp’s only properly trusted left-back (as seen with how the quick but clunky Brad Smith was briefly tested and then sold), and the Spaniard started this season with the manager’s full backing. But Moreno played himself out of contention, and now Milner is the 100% choice, with the ex-Sevilla man, while still liked by the manager, no longer an “equal” of the vice-captain. (The fact that Klopp still sings Moreno’s praises and says he’s been the best player in training shows that he still likes him. Again, a manager doesn’t say stuff like that unless he means it – not least because the other players would lose trust in the boss if it was patently not true to them during the week, if they were training better and harder. For instance, no one ever said Mario Balotelli was the best in training.)

So far I’ve found that there are also 13 “100%” players this season, but the key difference is that I would rate several of the non-100% players – those outside the favoured XI – as not being too far off: Origi at 90% (having dropped down slightly in the pecking order with Sturridge’s increased fitness – there seems a clear hierarchy right now); and Klavan and Moreno at 80%.

Even Simon Mignolet at 90%, but with this rating less to do with the keeper’s qualities and more to do with the fact that the first-choice (i.e. 100%) keeper – Loris Karius – is fairly young and new to the league, and that Mignolet hasn’t done anything wrong this term. If I were to reassess this later in the season it may be that Mignolet is back at “100%”, and by then Karius is someone Klopp avoids at all costs – although I presume he will be patient, and instead stick with his compatriot throughout the baptism of fire that comes with being thrown into the Premier League for a high-profile (and potentially title-challenging) team partway through the season.

So it still irks me now when people talk of inconsistency last season, especially with the heaviest schedule in Europe undertaken with a mixed-bag of a squad and the attempt at a change of direction in playing style and fitness. Until a couple of poor results, people were talking about the instant impact Pep Guardiola had made at City in no time at all, but he’d had a preseason with an expensive squad that included world-class players who were recently champions (2014), and he’d brought in half a dozen players and shipped out plenty more. (Even so, he should still be expected to improve with further time.) And comparisons with Brendan Rodgers ignore that Rodgers always had full preseasons, and started the job by instantly bringing in some of his own players.

Last season an astonishing 38 players made an appearance for Liverpool – 37 of whom did so under Klopp (only Joe Gomez missed out after he took charge) – and anyone looking for consistency or excellence in such a scenario is seriously deluded. The circumstances for consistency just weren’t there.

Crucially, players like Joe Allen and Martin Skrtel had become “60%” and “50%” players respectively – Klopp would use them, but he wasn’t working out ways to get them into the XI. He clearly liked Allen, but not quite enough. And of course, I assigned these players those subjective values in May, before the summer window opened, and it was therefore no surprise that they were sold. If Allen had been a 90% player for Klopp an effort would have been made to retain him.

You could say that this point that Klavan (80%) is clearly a ‘reserve’ Klopp would be happy to use, whereas Skrtel (50%) was almost avoided at all costs as last season wore on. These may not seem like big distinctions – two players at the same age, traded for roughly the same fee (c.£5m) – but Klavan has built a career on being the epitome of steadiness and on the flexibility to also play full-back, whereas Skrtel was either brilliant or hopeless, and only ever a centre-half. And of course, Skrtel, like a punch-drunk boxer, had become part of the institutionalised failure at Liverpool.

By the end of last season, someone like Kevin Stewart was a 40% player – used in what were essentially the B-team games, and a player who may have faded away with new arrivals (having started the season as maybe a 10% player, if that). Now, however, I’d guess that Stewart is up to 60% – Klopp knows he can trust him, and has already given him Premier League minutes this term; but also, if everyone is fit, Stewart probably doesn’t make the bench, let alone the XI.

A year into Klopp’s reign, it’s possible to see who he really likes and who he doesn’t, although almost all of the latter have been shipped out, and the sense is that, at this point, he rates everyone at his disposal. Others will still go on to disappoint this season – not everyone in a big squad can be at the top of their game all the time – but no one is of the wrong temperament or playing style for the manager.

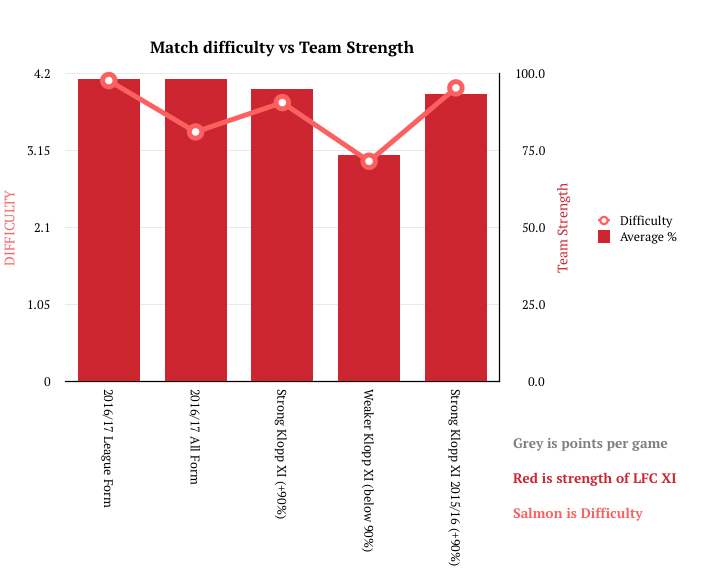

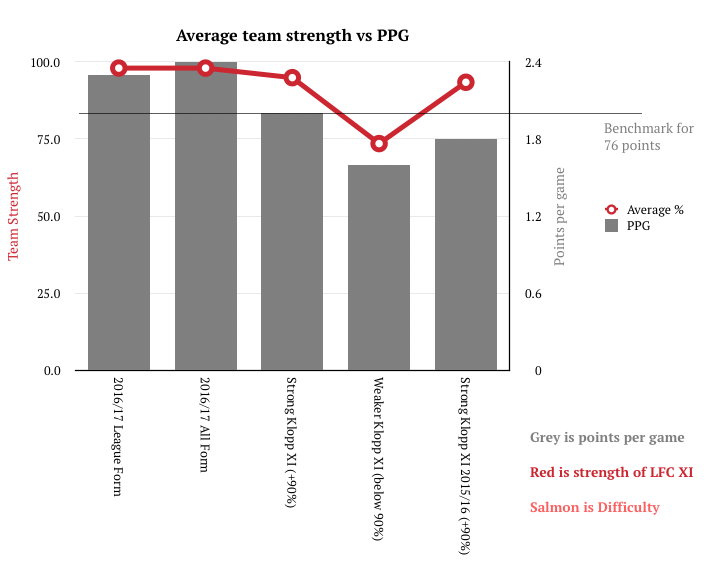

So, with this all in mind, it’s possible to look at the results his Liverpool have got with “strong” XIs – team averages on strength of what I perceive to be 90% and above. And while the numbers I use are clearly subjective, they are based on Klopp’s selections (with a hierarchy of choice easiest to discern at those points when everyone is fit), and which I believe are entirely logical.

It’s also possible to rank the difficulty of matches, using the system I devised at the end of last season for the article I mentioned, to see how Klopp’s tenure from October 2015 to October 2016 has panned out, given nine further games since the end of last term.

And what I said at the end of 2015/16 – based on Klopp’s excellent results when he could pick a strong team – seems to be backed up in what has happened so far this season, where every single selection (even in two League Cup games) has been over 90%, whereas last season he only fielded this kind of strength in just over a third of his games. In other words, Liverpool were either reasonably or significantly weakened in two-thirds of his games, for a variety of reasons.

The difference this season is that the “deadwood” has been offloaded, and now the bench is comprised of players Klopp really likes – we can all see that for ourselves, without the need to assign numbers (the numbers simply help to quantify it) – rather than the odd mixture of players left over from several previous bosses; and that although injuries and illness have kept out players like Mané, Coutinho and Firmino so far this season, it’s mostly been one player at a time, one game at a time, with no serious build-up of absentees and no key player out for weeks or months. And so we have a situation where Sturridge is finding it difficult to dislodge Firmino, but he gets into the team when any of the aforementioned trio are out, for no perceptible loss of quality – he’s just a different kind of top-notch player.

The difference this season is that the “deadwood” has been offloaded, and now the bench is comprised of players Klopp really likes – we can all see that for ourselves, without the need to assign numbers (the numbers simply help to quantify it) – rather than the odd mixture of players left over from several previous bosses; and that although injuries and illness have kept out players like Mané, Coutinho and Firmino so far this season, it’s mostly been one player at a time, one game at a time, with no serious build-up of absentees and no key player out for weeks or months. And so we have a situation where Sturridge is finding it difficult to dislodge Firmino, but he gets into the team when any of the aforementioned trio are out, for no perceptible loss of quality – he’s just a different kind of top-notch player.

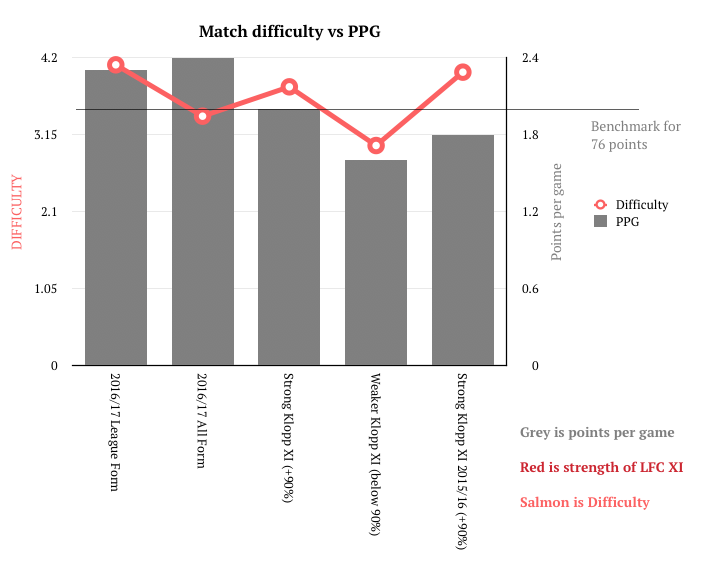

In the 19 “+90%” games of last season – the strong selections – the Reds averaged 1.8 points per game (with cup results converted to points), which is pretty decent but unspectacular. However, the difficulty rating for these 19 matches on a scale of 0-6 (with 0 being at home to abject opposition; 6 away to the very best sides) was 4.0, clearly above the “normal” range of fixtures of 3.0. (The difficulty rating was essentially a simple 1-5 in terms of opposition quality, with 1 point added if away, and 1 point deducted if at home.)

This is because Liverpool didn’t have a normal season. In a 38-game Premier League season you face the full gamut of opponents, home 19 times and away 19 times, and there’s a 3.0 average. And of course, Liverpool haven’t had a normal season this year either – at an average of 4.1 in the league based on seven matches so far, five of which were away, with four of the seven games “big” clashes.

Last season, Liverpool faced two extra matches against Manchester United, which are always tense occasions – results before and after can be affected by the spectre of such clashes. There was a League Cup final against Manchester City, and again, you can expect some “conserving” before such encounters, and I think the League Cup can be a poisoned chalice because a cup final mid-season is destabilising (logically, they should always be at the end of the season, but there’s no room with other cup competitions).

Liverpool played Borussia Dortmund twice, which was a gargantuan test – with the euphoria of winning against all odds followed by the low of the comedown that follows any high. Liverpool then played Villarreal twice, and as such, to lose 3-1 at Swansea in between these games becomes more understandable – it’s not a mark of inconsistency but merely a reality of sporting life. And to draw 1-1 at West Brom (with nothing at stake) three days before the Europa League final against Sevilla is equally understandable. As I said in May, this was the fog that shrouded the true quality of Klopp’s Reds.

The difference this season is that in the seven league games – with a difficulty rating almost 40% greater than the norm – the Reds have average 2.3ppg, or 87 points pro-rata. (And that ppg would therefore be higher if I added some weighting on account of the fixture difficulty – you don’t play a 38-game campaign that includes Chelsea, Arsenal, Spurs and Leicester six times, and which has 30 away games and only eight at home.)

Add the two relatively easy away cup games and the difficulty level drops to 3.4 from 4.1, but the ppg rises to 2.4, or a 91-point season pro rata on 38 games.

And again, even this 91-point season would still be tougher on paper than the norm, with the clear weakness of Burton and Derby (away) still not fully mitigating the five Premier League away games and four big clashes, out of seven played. None of this is to say that Liverpool will go on to hit 90 points – even with a good tailwind that seems unlikely, and we must always expect the unexpected – but it puts the quality seen in the season so far into context.

Add both seasons together, to form the entire 28 games where Klopp has fielded a +90% team, and the average is 2ppg – worthy of a 76-point season – but again, that’s with a difficulty ranking about a third higher than the norm (and a Klopp 100% side last season was not as good as his 100% side this season).

By stark and revealing contrast, the 33 games where he fielded (by choice or otherwise) weaker XIs yields just 1.6ppg (equivalent to a 61-point pro rata season), even though the average difficulty of those fixtures is bang-on the average of 3.0. Again, as noted, due to squad reconstruction and a lack of an injury crisis so far in 2016/17, none of these games is from this season.

Look at the following three graphs, in case my words haven’t convinced you. Each graph has two axes, covering two of the three different measures: average XI strength (out of 100%); average points per game (range of 0-3); and average match difficulty (0-6). So closely do the results mirror each other that I had to triple-check if I wasn’t just using the data from the previous chart.

For the charts, grey is points per game; red is strength of LFC XI; and salmon is fixture difficulty.

It gets slightly confusing in terms of the overlap in results because last season Klopp tended to pick his strongest XIs for the toughest games – which makes sense, given that he wanted his best players fit for the massive match-ups, which came thick and fast, and when it came to the likes of Exeter in the cup, or league games sandwiched between massive European games, he had little choice but to heavily rotate. A manager totally happy with his squad, with a greater number of trustworthy players in reserve, doesn’t have to scrape the bottom of the barrel in terms of selection, injury crises aside. Remember, this was also a manager learning about his players, from the established to the youthful prospects.

We see that his points-per-game was better in the big matches – leading to to certain perceptions – even though the difficulty was greater, because his XI was stronger. People obviously said that Liverpool only got “up” for the bigger games, but the squad was spread far too thinly in many other encounters. When his XI was weaker, even though the games were easier on paper, the points per game dropped off – Liverpool were there for the taking, often in unfamiliar line-ups (and not because they weren’t up for it).

Again, this is due to the abnormal number of tough cup fixtures, where Klopp had to balance fitness concerns with winning the most important matches as the season unfolded – and priorities shift depending on what’s happening. After all, we can all say the league is the priority, but that was already “lost” when Klopp arrived; and who would have wanted him to go all-out versus Swansea and West Brom when, given that it was May, they’d become meaningless compared to the Europa League?

The only disappointing points-per-game figures within my breakdown come from last season; the first two columns on the graph are from this season, and they show that the Reds have an above-average PPG despite above average fixture difficulty.

One other thing I looked at in my article from May was an allowance for Klopp’s newness (and therefore the lack of time to fully address fitness and tactical issues) that diminished with time passed – and this again only highlighted that his effectiveness was masked.

It showed that the stronger XIs he picked early on didn’t necessarily know how to play the Klopp way; or if they did, they didn’t have the stamina to do so adequately. They were strong on paper, but not strong on understanding and fitness; both of which would logically be better by the spring months. In between – around December time – came an injury crisis. At this point there was neither understanding nor fitness, and in many cases, weaker player selections.

With the passage of time, results for his best XIs did indeed improve; but with time came more fixtures, more rotation, and more weakened XIs, which muddied the waters.

Now…

Now, even with three or four injuries the XI-quality can remain above 90%, whereas last season it couldn’t. To put in Origi now – the third-choice centre-forward behind Firmino and Sturridge – would be nothing to worry about; whereas last season, to put in Benteke – for whom the team was not set up, and where the player was lacking confidence (and carrying a big price tag) – was to clearly weaken the XI.

The challenge this season will be when players like Lucas (best days behind him, certainly as a midfielder), Klavan (very good but not elite), Stewart (improving but not yet a major force), Ings (good player but not elite, and hasn’t started a senior game in a year after serious injury), Ojaria (a possible future star but only 18) and Grujic (massive potential but still only 20 and adapting to England) are all called upon – either all together, or three, four or five them at the same time. Suddenly the XI will clearly be below 90% – these are, for now, back-up players, along with one or two others.

But of course, there aren’t likely to be sufficient games to throw these in, as Klopp has kept it strong even in the League Cup (because there’s no Europe on top), and with less likelihood of an all-out injury crisis with no chance of another 63-game season.

We also shouldn’t be seeing too much of the equivalents of Brad Smith (quick but raw and limited), Adam Bogdan (nervous wreck), Jose Enrique (totally disinterested outcast thrown into a few cup games), and even Christian Benteke (good Premier League striker totally unsuited to the manager’s style) – because no such equivalents are anywhere near the squad. Even the worst players this season should be much better than the worst from last season, and there will be nobody hopelessly out of kilter with the manager’s ideas.

Again, this is not being wise after the event – all this was covered in the article from May.

The second part of this article is for subscribers only.

PART TWO

Liverpool At Their Best Under Klopp Look Sensational

https://tomkinstimes.com/subscribe/