https://tomkinstimes.com/2021/02/the-mother-of-all-black-swans-in-a-tailspin-ttt-subscribers-writers-give-the-real-reasons-for-liverpools-league-struggles/

By Paul Tomkins, Chris Rowland, Daniel Rhodes, Andrew Beasley and various members of the TTT community

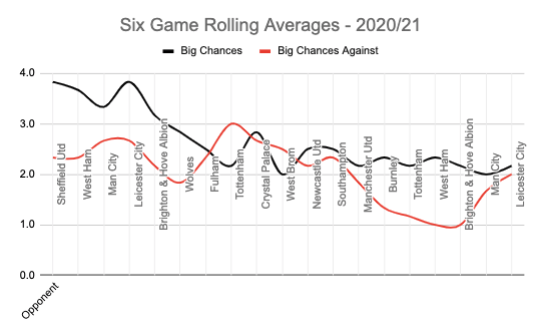

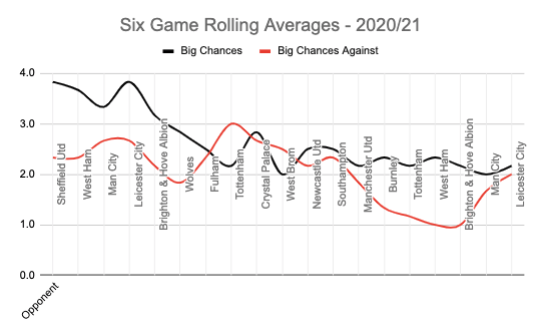

Liverpool got back on track with a very impressive away win against German neo-giants Leipzig – although the stats showed that the Reds have been lucky defensively in the Champions League (teams not taking their big chances) and unlucky in the league (opposition teams taking more of their chances than last season).

The league form continues to be well below expectations, for a whole host of reasons that– as this site’s writers and commenters – we will try to unpack below. This piece aims to add to previous attempts like my dismantling of the arguments of numpties like Roy Keane), with new dimensions, and with the intention to try to think of every last thing (whilst obviously accepting that such an undertaking, in a season of so much craziness, is nearly impossible).

A lot of the issues can be dated back to the utterly insane game at Goodison Park, so it’s timely that the return fixture takes place this weekend. (How many Liverpool players will Jordan Pickford and Richarlison try to maim this time? What a shame the Kop will not be there to give them a warm welcome!)

We’ve also tried to collate many of the most illuminating graphics and charts that we’ve created or which we’ve stumbled across, many of which have appeared in other TTT articles – but the aim here is to try and make this article as close to a full health check for the Reds from a team of medics, rather than a cursory glance from a distracted doctor. (Even then, we won’t catch every little ailment.)

Subscriber Tony McKenna first introduced us on TTT to the Black Swan a decade or so ago, and this is a piece he wrote in 2014 on the issue:

Based on the work of Nassim Nicholas Taleb, the Wikipedia definition is that:

“A black swan is an unpredictable event that is beyond what is normally expected of a situation and has potentially severe consequences. Black swan events are characterised by their extreme rarity, severe impact, and the widespread insistence they were obvious in hindsight.”

Chris Rowland: To say much has been made of Liverpool’s travails lately would be an understatement worthy of calling the Atlantic a ‘whole bunch of water’ (copyright Terry Gilliam, Monty Python!).

Little of it has been analytic or in-depth, or taken any account of context. Or even got the basic facts right. Just damn them with generalised and superficial cliches and pretend that’s job done.

Example: Martin Keown after the Leicester away game:

“That central defensive position is where the problems lie.

“Klopp has lost defenders and taken two midfielders out into the defence. That is four changes from the team who did so well and he doesn’t need to do that. It is too many.

“Without Gomez and Van Dijk they have one hand tied behind their backs. The wheels have come off. Klopp needs to get that position sorted.”

Fact: but it wasn’t just Joe Gomez and Virgil van Dijk missing injured was it? It was also Matip, Fabinho and new signing Ben Davies. Fabinho couldn’t have played in midfield, or defence, or anywhere else!

Henderson and new signing Ozan Kabak played centre-back because the only other two available were rookies Rhys Williams and Nat Phillips, neither blessed with great pace. Against Jamie Vardy and Harvey Barnes! Really? But that typical combination of ignorance of the full facts and failure to consider context, both of which Keown’s comments graphically illustrate, are the sort of reason why we decided to compile this article. So instead of blithely saying ‘he should get those positions sorted’, perhaps he should try suggesting how, within the confines he has to work in. That might be worth listening to.

When it comes to understanding and investigating the real reasons for Liverpool’s demise this season, TTT subscribers are in the habit of digging deeper, and examining context, of looking at the factors that are having an influence, and providing the data to back it all up.

So here is a round up of what TTT subscribers have had to say lately about the main reasons why Liverpool, after two seasons of 97 and 99 points, two consecutive Champions League finals, a World Club Championship and a European Super Cup, are finding those impossibly astronomic standards hard to match this time round.

‘Excuses’, as Roy Keane, Richard Keys and keyboard warriors with the attention span of an aubergine might say.

Or ‘extenuating circumstances combining to produce an inevitable conclusion’, as TTT subscribers might put it.

This in-depth read includes ground covered in other TTT articles, but also offers a more focussed rundown of the issues.

Overview

First, a summary from Aquaman:

Like many of you I’m sure, you’d be part of alternate forums like Twitter (which can swing to the extremes as fast as you can type your tweet mid sentence before posting) or WhatsApp groups (probably a set of closer friends you know). And the general narrative I’m seeing right now [so ignoring the obvious lunatics and those turning on the club and players] from these forums is that:

1. The officiating is utter nonsense and blatantly against us

2. Our injuries are deep rooted enough to expect not challenging for the title

These are independent narratives. It’s either or. But the reality is, each of it (and a few more factors) mesh together to make this the perfect storm. I’ll throw in another cliche. Each are dominoes that causes the next.

1. Pandemic

2. No crowds caused by pandemic

3. Compressed schedule caused by pandemic

4. Physical fatigue caused by compressed schedule

5. Injuries caused by fatigue

6. Bad officiating caused by no crowds (to a certain extent)

7. Injuries caused by bad officiating

8. Mental and emotional fatigue caused by bad officiating

9. Mental and emotional fatigue caused by physical injuries distributed within squad

10. Emotional fatigue caused by pandemic

11. Slow reinforcements caused by no crowds (no income) and pandemic (inflated prices)

I’m sure I’m missing a whole lot more, but it is indeed a Perfect Storm and our bright red ship is right now in the middle of it. And like all storms, you’ve got to ride it through, provided your ship is fundamentally a steady ship with a steady crew.

Crisis? I’m not sure we are in one yet because, as the underlying numbers and even our naked eye tells us, we’re still playing good football. The players are still playing for Jürgen. The owners haven’t deserted Jürgen (although there’s arguments that they should’ve been a little bit more flexible with earlier reinforcements, but hindsight’s always great, eh). Jürgen’s coaching team are still loyal to him. So, our ship is fundamentally steady. Our crew are fundamentally steady.

But why, as other clubs cheerleaders and our own doubters would ask as they scream joyously, is this a unique storm just for Liverpool Football Club? The pandemic and bad officiating is prevalent to all. It’s because they see the two narratives above as independent, and not see the whole storm, it’s full force of nature, and all the contributing factors leading to it.

RDucker: An extract from an article found on The Athletic. It seems we are much less likely to play a risky pass this season, compared to all seasons under Klopp. The author provides two examples in the City game when City were defending facing their goal but rather than play the ball forward we played it sideways, allowing City to get in a proper shape.

“The speed in which Liverpool typically turn defence into attack is what you most associate with a Klopp team. Using this transition to quickly get a shot at goal with the speed of their front three has been consistently strong, but interestingly this has dropped off this year.

Looking at the directness of the attack, we can see Liverpool were taking a shot 3.6 times per 90 minutes within 15 seconds of recovering the ball. As expected, that put them top of the list in the Premier League for direct attacks from front to back.

This year, their numbers are lower and, interestingly, the lowest of any season under Klopp. They are now average 3.0 shots per 90 within 15 seconds of recovering the ball — which puts them fourth in the league behind Leeds United, Manchester United and Aston Villa.”

“Liverpool are holding onto possession for two seconds longer this season than the last one. This might not sound like a lot, but it could be the difference between catching the opposition out of shape or not. Many might point to this change coinciding with the introduction of Thiago Alcantara into the team — it will be interesting to look closer into this once the Spaniard has played a larger number of games than his current eight league starts.

Likewise, the slower tempo is shown by more of their possessions consisting of at least nine passes compared with last season. Given how Liverpool typically like to play at breakneck speed, this difference is all the more noticeable.”

Paul Tomkins: regarding RDucker’s post above, as Thiago has barely played, it’s funny the author of that Athletic piece should mention his name, even if it’s to say that he may not have played enough. Personally, I think Thiago as a problem (beyond his dreadful sliding tackles) has been a red herring. To have only played a few games at the time the piece was written seems to prove that he can’t have slowed Liverpool down across the season. Also, he’s been one of Liverpool’s best pressers, so it’s not like he’s slow in that department.

Rather than it be any desired change, the team is different in so many ways from last season, due to injury, lack of preseason, etc.. I think it’s a valid observation – if the Reds have indeed been making more passes, then that is something to highlight to be aware of – but I don’t always agree with the conclusions: it could be game-state related (you may pass more or less depending on whether you are leading, drawing or losing), or many other things (including a lack of energy due to injuries and a lack of preseason, plus the loss of Virgil van Dijk’s pace-injecting long passes). For instance, if your best dribbler is out, your team may suddenly dribble less – it’s not that you can tell lesser dribblers to just go out and dribble like an elite dribbler.

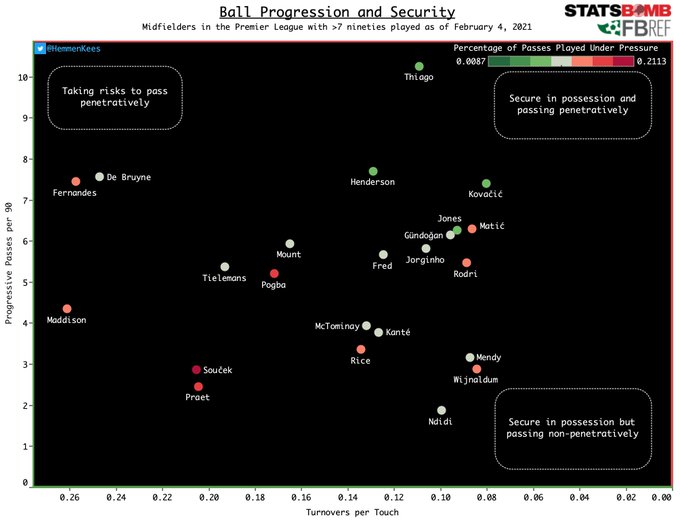

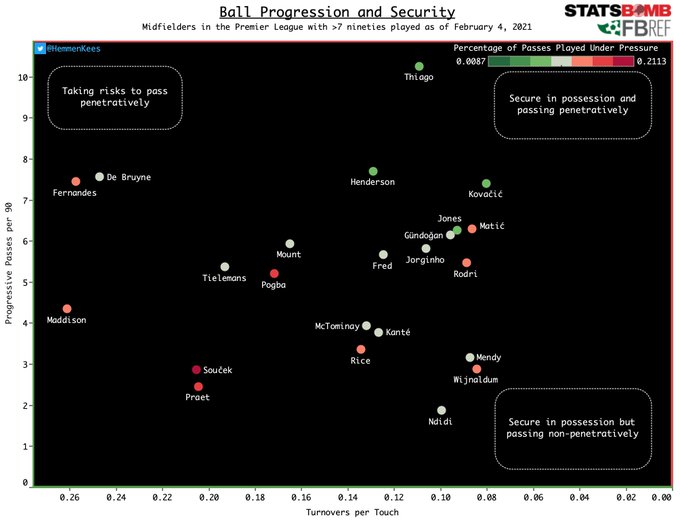

Liverpool had games with over 900 passes last season (and won), and as we showed last week on the site, Thiago is miles ahead of anyone else in the Premier League for “progressive passes”. But so many things have gone wrong this season, which will be covered in this hive-mind piece. Even so, this Thiago graphic by Dutch data visualiser Kees van Hemmen is well worth another outing:

It’s also worth remembering how many of the Reds’ best pressers are not available right now. To ask for more energy is one thing (even when players are fatigued), but some vital pressers are injured, or have been injured for long parts of this season, as shown via this Anfield Index: Under Pressure tweet:

Set-Pieces

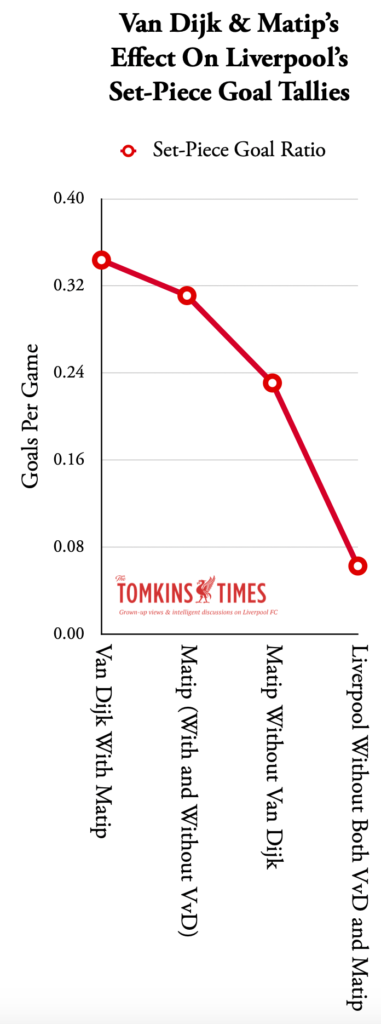

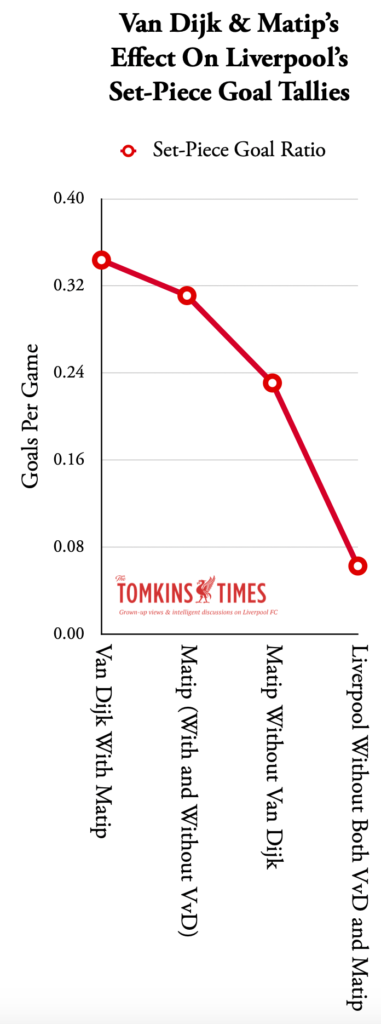

Paul Tomkins: No one else seems be picking up on how Liverpool have gone from elite to toothless at set-pieces due to the injuries to all the tall players. To focus only on van Dijk is wrong for a number of reasons, but obviously he’s a key player for the Reds in both boxes, and in starting moves. Indeed, his beautiful, defence-turning long-range passing has been sorely missed.

He also is worthy of a mention in terms of leadership effects by Dan Abrahams [covered in a post that appears later in this piece], but there are other players too, whose absence is costly.

There are so many factors, and it’s hard for simplifying soundbites on what’s wrong.

This (below) was a graph I created before the Leicester game, which saw another 12 corners – often well-delivered – easily defended.

I first introduced this graph on the TTT Substack Newsletter (click on the link to sign up). Remember, this is not the goals the tall duo score, but how many more goals the team scores from set-pieces (half of which the tallest duo directly contribute to, the other half they take up the time and energies of the opposition’s best markers to leave others free).

I’ve shown that we’ve scored one set-piece goal in 16 games without the Reds’ biggest two centre-backs, having averaged a 1-in-3 when both were in the team, and 1-in-4 when it was just Matip and no van Dijk. (Since I created the graph, it’s now one set-piece goal in 18 games without both van Dijk and Matip – pro rata, that’s the equivalent of just two set-piece league goals per season, when last season the Reds scored twenty. The effect on the goals column is the same as replacing Mo Salah with an ageing Rickie Lambert or a disinterested Mario Balotelli.)

I’ve shown that we’ve scored one set-piece goal in 16 games without the Reds’ biggest two centre-backs, having averaged a 1-in-3 when both were in the team, and 1-in-4 when it was just Matip and no van Dijk. (Since I created the graph, it’s now one set-piece goal in 18 games without both van Dijk and Matip – pro rata, that’s the equivalent of just two set-piece league goals per season, when last season the Reds scored twenty. The effect on the goals column is the same as replacing Mo Salah with an ageing Rickie Lambert or a disinterested Mario Balotelli.)

In addition, the Reds’ strikers had a collective drought for the first time since they were formed as a trio, and sooner or later that had to happen. While they missed a ton of chances, at the other end teams took their chances, in contrast to last winter, when Liverpool got lucky as the opposition squandered chance after change in December and January (but where the psychology of the team was different, and it probably made opponents more nervous, in contrast to now, where the same has applied to Liverpool).

I’ve been very critical of a lot of Liverpool’s finishing and final passes in 2021, but I also don’t blame the manager, and don’t really blame the players most of the time, as these things come and go, and if you’re low on confidence you’ll tend to miss chances, or mess-up crossing and final passes.

Andy Robertson has been very poor on the ball, but as Jamie Carragher showed on Sky’s Monday Night Football, he’s played 95% of all PL minutes since the summer of 2018. Trent Alexander-Arnold hasn’t been as effective, and he’s been both ill and injured this season. To use 17 different centre-back partnerships, and 13 in the Premier League in just 24 games, must be some kind of world record.

So it’s not just players who are back fit – Alex Oxlade-Chamblerlain has been terribly off-form, as he has the opposite problem of not playing for six months and then needing to find his touch, and being off the pace of the games (and now he has more games in his legs, he’s coming off the back of those rusty showings that haven’t helped him). If the team is riding the crest of the wave you can more easily just jump onboard.

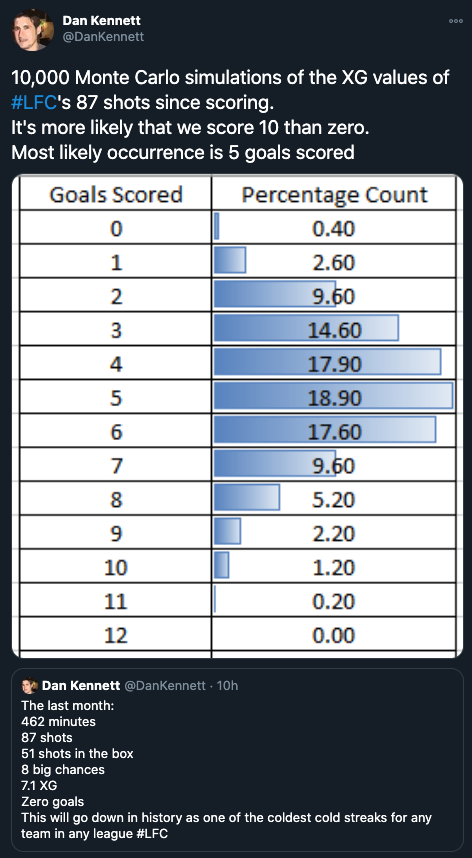

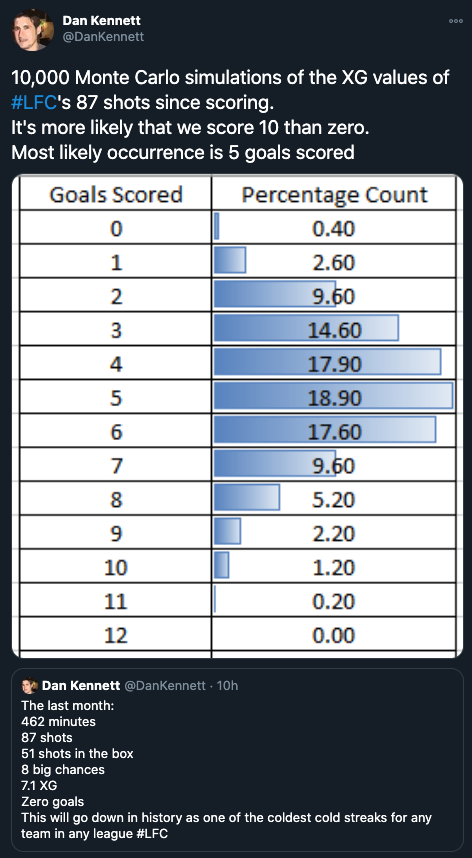

The finishing in general had a really weird run (which is continuing in open play in the league at Anfield), as TTT alumnus Dan Kennett shared a few weeks ago:

The more chances missed by a team that is under serious pressure (either to win things or to escape relegation), the greater the pressure grows, in a negative feedback loop. Missing chances breeds anxiety, which leads to snatching at chances. In addition, what headed set-piece attempts the Reds have had have often been quite tame, in part because they have been from smaller players battling to get an effort in when up against bigger, stronger players.

Injuries

Chris Rowland: First, some figures:

Nineteen (must resist the Paul Hardcastle reference) different Liverpool players have been injured this season. Nine were missing through injury at Leicester, and Milner limped off after 17 minutes with a hamstring injury to bring it to double figures. Afterwards, James Maddison made the point that Leicester had injuries too. They had – just not as many, and not all in the same positions. The extent of the two sides’ injury situations was not comparable.

In the match at Leicester on February 13th, Liverpool fielded their 17th different centre-back combination of the season. In a total of 34 games in all competitions.

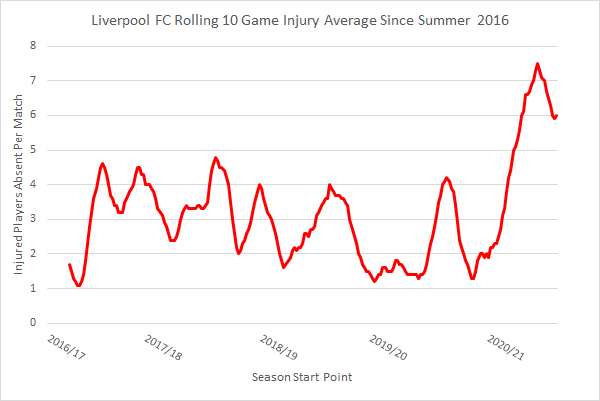

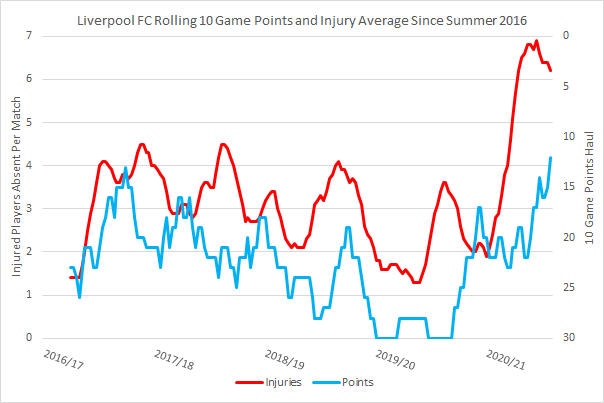

Andrew Beasley has shown that the greater the number of players out injured, the less chance there is that Liverpool will win, to an uncanny correlation, based on Klopp’s career at LFC since 2016.

He also showed that, as things stand, the longest run of any centre-back pairing this season is … 2.5 games! “Phillips and Henderson played the second half against Spurs, then the full matches against West Ham and Brighton. The longest run of starts is three, for Gomez and Fabinho. But Fab had to come off after 30 minutes of the third game.” If Henderson and Kabak play together beyond half-time at the weekend, they become the longest consecutive partnership for the season.

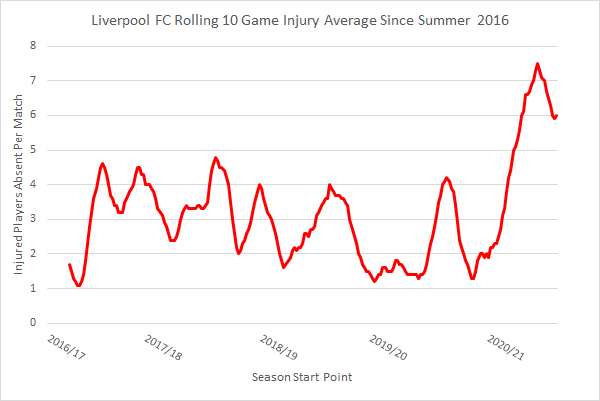

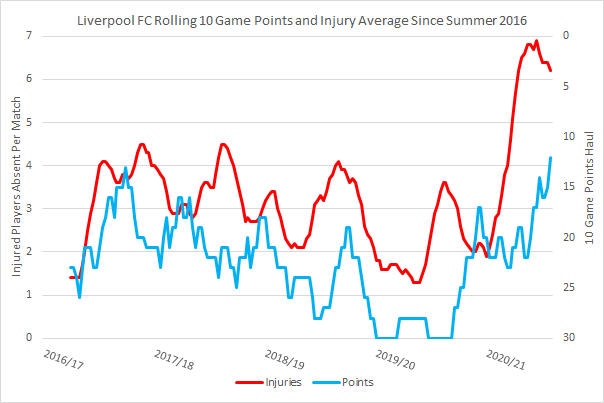

First, just look at the injuries (which this season are double any of Klopp’s previous seasons), and then, with the points scale inverted to show “good” vs “bad”, how they have affected the Reds’ form.

Now, with the rolling form overlaid:

(Again, the blue line is inverted, so that “good” is lower, and “bad” is higher.)

Jürgen Klopp in his Leipzig news conference, covered the stark reality:

“All the weeks and months you can see easily it is a mix of different things that happened. Now is not the time to explain,” he said.

“Injuries have played part in it, you can’t ignore them, it changed everything.

“Its like building a house, if the foundations are not right things are a bit shaky.

“We cannot change things but we will work on it.”

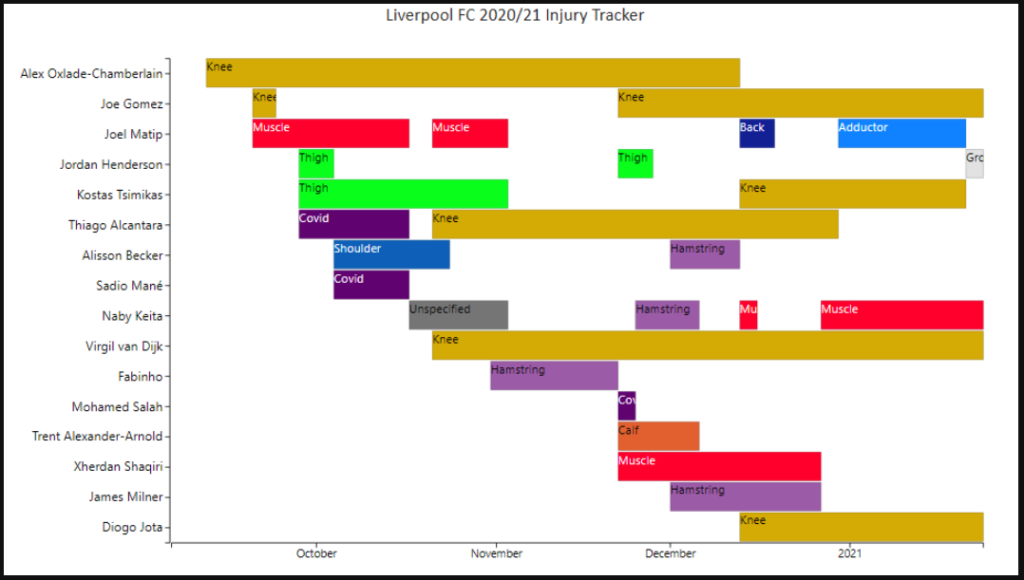

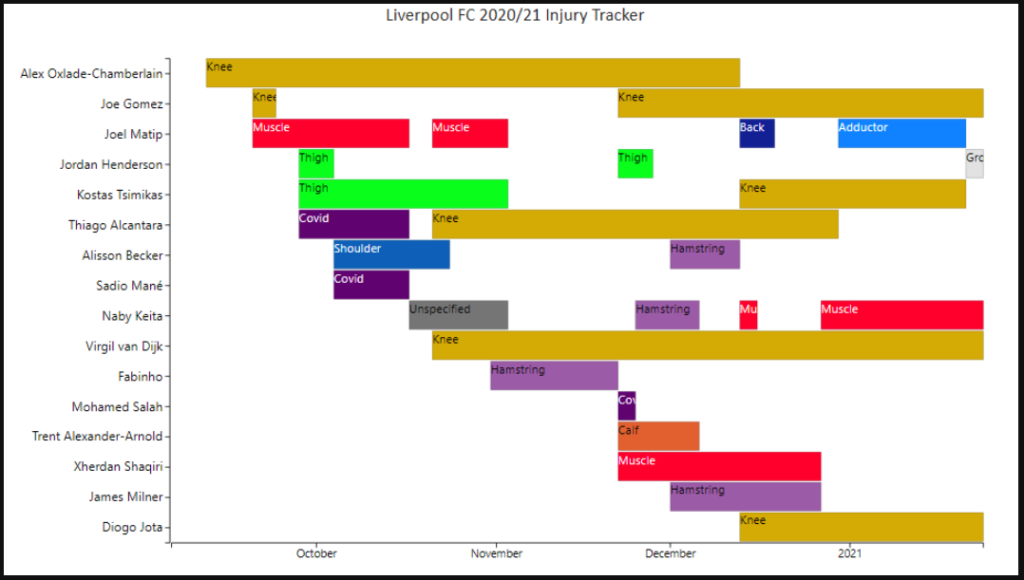

This was also Andrew’s graphic from a few weeks ago, that gives a sense, visually, of how great the disruption has been. Since then, injuries fell to five one week, then ten more recently, before dipping back to seven for the Leipzig game.

RDucker: Some points from a sports psychologist on the impact on injuries on other players: (from The Athletic)

“Dan Abrahams is a golfer-turned-sports psychologist, who has previously worked for Bournemouth and the England rugby union team as well as with players at West Ham, Fulham and Derby County.”

“Injuries to key players create a different narrative across an organisation,” Abrahams says.

“It makes a difference to the emotional temperature in a dressing room and can result in anxiety. There are people who are game-changers with their mere presence. Their presence alone can lead to a release of testosterone in (other) players’ bodies and the adrenaline to perform.

“It’s that feeling of looking across, seeing someone like Van Dijk and knowing he’s going to help you. If you’re a defender who has played next to another defender hundreds of times before, you have that understanding about what they’re going to do, where they’re going to be. That’s going to make a difference to your perception action. Without someone like that, confidence and understanding reduces and executing game plans becomes harder.”

More Injuries Were Inevitable

It seems that any team can expect a 25% increase in injuries when playing so many games. Sometimes a team may have a 15% increase, other times it may be 40%. The average is 25%.

So, Liverpool already had several out injured when going into this recent phase, which is just another such run of games for the Reds in 2020/21. The remaining fit players, with less scope for rotation, are at an even greater risk than if everyone was fit to start with.

Research conducted by artificial intelligence platform Zone7, which specialises in injury risk forecasting and works with 35 professional football teams worldwide, shows that playing eight matches in a 30-day period increases the incidence of injury by 25% when compared with playing four to five matches in the same timeframe.

And remember, Liverpool have had seven serious ligament injuries, three of which have ended seasons and another three of which were at least three-months out – all six of those most serious ones to senior players – and that is not down to bad preparation or bad physios; it’s pure bad luck, especially if it was the result of a shocking foul.

Finally on injuries, this is worth repeating, relating to how it’s not losing your first-choice that really hits hard, it’s losing the 2nd and 3rd choice players as well:

Lubo:

“A point on the injuries to Gomez and Matip on top of that of Virgil. Ryan O’Hanlon writes an email newsletter and in his latest one, on Liverpool (he is a fan), he mentioned a study of NFL teams that looked at defenses and found out that it’s not an injury to you your first-stringer (top defender) that kills you, it’s the injury to the second and third backs ups that sink you, as that means you now have to play your fourth and fifth options and those are just never that good. Had Gomez and Matip stayed fit and healthy, and allowed us to play Fab and Hendo in midfield more often, it would be a completely different story. Alas. Here is a link to the study, btw, though it is paywalled.

Enforced Rookie Minutes – What Has “Killed” Liverpool

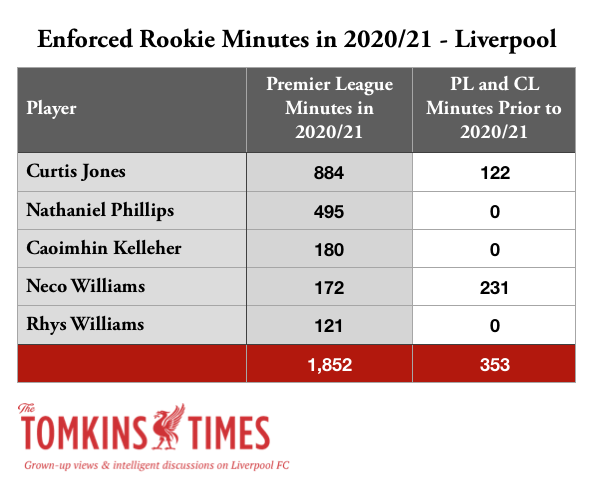

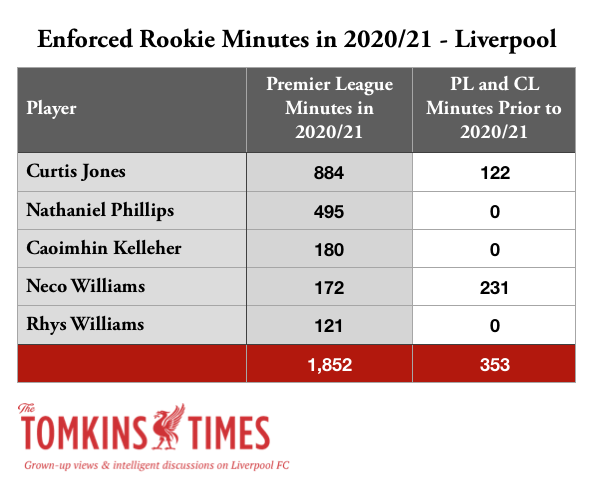

Paul Tomkins: While I have touched on the issue before (along with factors like the massive loss of aerial ability due to injuries), I thought it was worth looking in more depth at how many minutes have been played by “complete rookies” in the Premier League for Liverpool this season.

I defined a “complete rookie” as anyone under 23 who had never played a top-level game before, or who had previously played fewer than 600 minutes in the Premier League (or equivalent level in the other major leagues) and the Champions League combined, going into 2020/21.

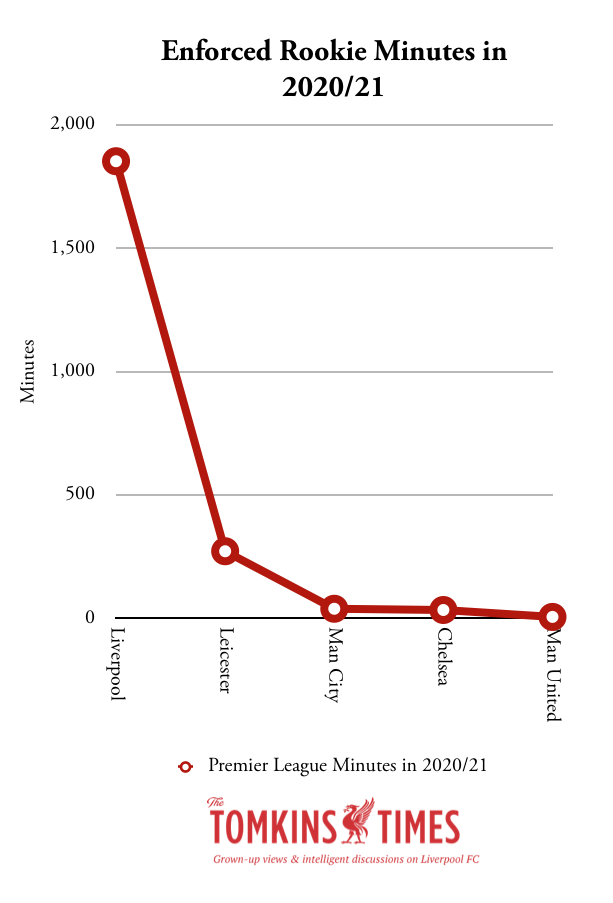

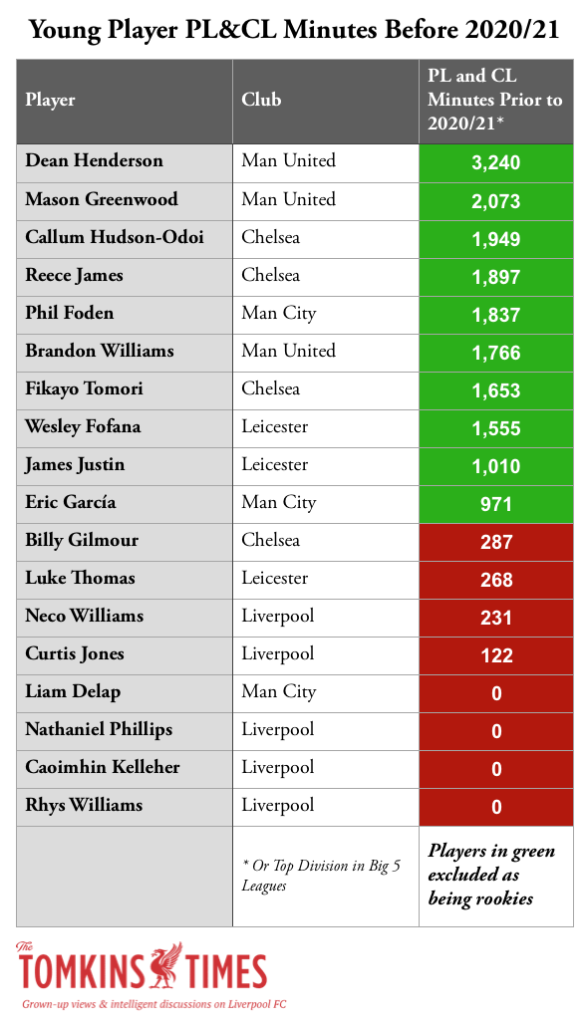

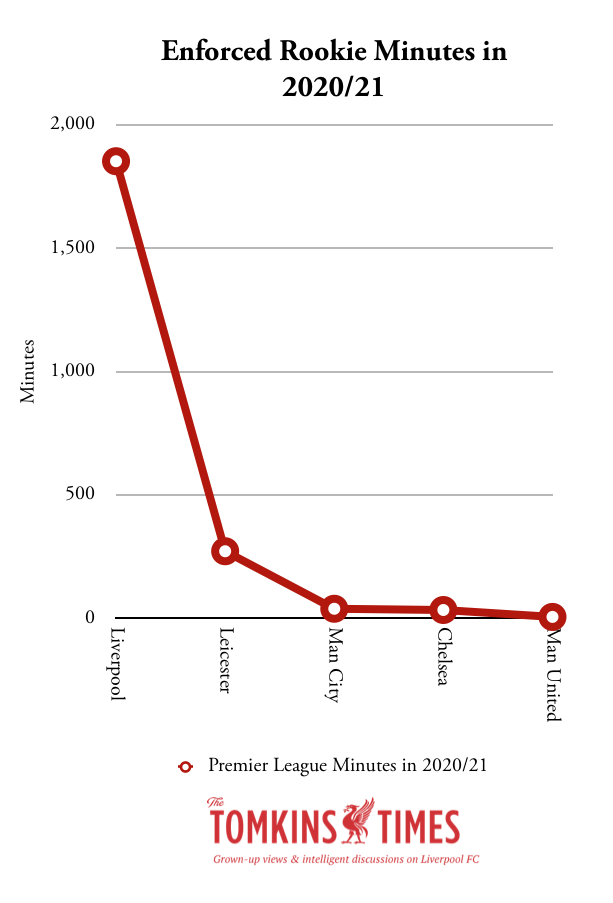

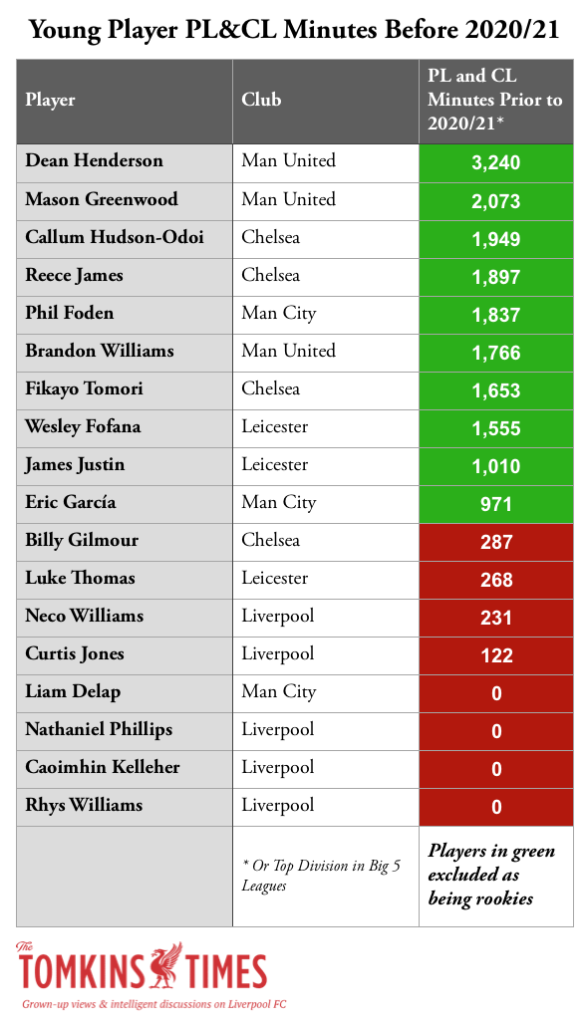

As it turned out, I could have set the “rookie bar” anywhere between 300 and 900 minutes played prior to 2020/21 and still got exactly the same results. A lot of young players at rival clubs had played more than 900 minutes prior to this season; and across the top six (minus West Ham) there were eight rookies with less than 300 minutes. Five of those eight were Liverpool players.

I didn’t include domestic cups, as so many players get minutes in those competitions, but the standard of opposition faced can range from a top Premier League side to non-league opposition. Even the Championship and League One clubs rest players for the FA Cup and League Cup. And as Liverpool have had no real domestic cup runs in years, it’s not exactly been a chance to play the kids very often (unlike Man City and their regular easier fixtures that offer them little trouble, and are ideal for some rotation and some rookie-blooding).

To play in the Premier League or Champions League, unless in dead rubbers, is a mark of confidence from the manager, or a situation where no one else has been available.

In 2019/20, Chelsea, Manchester United, Manchester City and Leicester all had mixed seasons. Many of those clubs – the ones who are Liverpool’s closest rivals in the table right now (assuming West Ham will fall away) – played a lot of younger players last season. By contrast, this season they’ve played hardly any rookies, with most of last season’s rookies now considered experienced enough to qualify as senior players.

Frank Lampard, with a club transfer ban, was famously given leeway to blood some youngsters, and Manchester United had fielded Mason Greenwood and Brandon Williams for almost 4,000 minutes of football prior to this season. Someone like Mason Mount played over 3,300 minutes for Chelsea in the two major competitions last season, and at 22, he’s clearly not even contention for inclusion as a rookie, as he seems to start no matter who else is fit. Phil Foden is moving to the level of first-choice, after nearly 2,000 minutes in a City shirt (in the major competitions) up to August 2020.

By contrast, the five rookies Liverpool have relied on for almost 2,000 Premier League minutes this season had just 353 minutes combined in the Premier League and Champions League in their careers up to August 2020. The graph below is another staggering example of what has beyond Klopp’s control. (You could argue that the club should have had an even bigger squad – despite the wage bill already being maxed out – but with 6-12 players out injured for most of the season, it’s less about squad depth and more about going beyond the usual limits of a squad, and raiding the U23 team.)

Now, you could rightly point out that Curtis Jones is playing better than a mere rookie, and you’d be right. But if the fit midfield pool (which wasn’t also covering for centre-back injuries) had included Jordan Henderson, Fabinho, Gini Wijnaldum, Thiago and Naby Keita, would Jones have 884 Premier League minutes this season? No way. He’d probably have 200 at most.

Equally, if Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain hadn’t returned so rusty after six months out, and Thiago hadn’t missed several months after the second serious and season-changing assault at Goodison Park, Jones would have had fewer chances to shine, and even now, is still perhaps between 5th-9th choice. (I’ve discussed in comments on the site this week what a great player Jones is, and his incredible potential. But he’s still learning.)

He could now arguably keep James Milner (based on age, depending on the midfield role) and Oxlade-Chamberlain (based on form) out the side, but not Henderson, Fabinho, Wijnaldum, Thiago or Keita, if all were fit, sharp and available for the midfield. He might usurp Keita if Keita can’t get back to being fit, but at best, he will remain below at least four others for the three starting midfield berths.

Liverpool, and Jones, have gained from almost 900 minutes of league action, but as good as he can be, he’s had costly moments and some poor games, because he’s just turned 20 and this is his first proper season. What he’s doing for most of this season for a lad who was just 19 when it started has been superb, within the context of a rookie; but despite his flaws that have at times cost points, this is a transitional season for him: his first as a proper first-team contender. This is a teething stage, for him and the team.

He’s learning on the job, and learning with some speed. But players like Mason Mount, Phil Foden, Callum Hudson-Odoi and Mason Greenwood had each played thousands of Premier League and Champions League minutes prior to this season; Jones had played a paltry 122 minutes, or less than two games’ worth of time on the pitch.

Neco Williams probably wouldn’t have got a single minute (perhaps bar a few late-in-game introductions) if Trent Alexander-Arnold had been fit all season, and Caoimhin Kelleher, as good as he’s been, only played because Alisson was injured and Adrian – the no.2 at the start of the season – looked shaky. Without doubt, neither Rhys Williams nor Nat Phillips would have played a single minute had Liverpool’s first four centre-backs not all been injured, three of them seriously. Both have had very good games, and clumsy games. That’s often what happens.

I created the following chart just to show why I’m not including certain players (in green) as rookies, and the contrast with those, in red, who are clearly very inexperienced. Liverpool have relied on five rookies this season in the league; combined, the other four clubs have used just three (and Liam Delap of City literally just got 39 minutes in one game this season).

And although he’s only 20, I’m not including Ozan Kabak as a rookie, after two seasons in the German top flight (over 3,000 minutes played in the Bundesliga, in addition to playing 360 minutes in the Champions League with Galatasaray and 1,000+ minutes in the Turkish Super Lig, and seven full caps for Turkey), although he’s obviously in an unenviable position of having to step straight into an unsettled defence – in a new league – within a week of his arrival; and the lack of understanding with teammates that contributed to the Reds losing at Leicester.

(The second goal came about – and listed officially as a Kabak error – because he would probably not have been used to a sweeper-keeper clearing up so far out of his box, and maybe didn’t hear the call, or if he did, quite believe what he was hearing; these are issues that a settled defence do not have to deal with, as everyone knows each other’s game. It’s not just about shouting “keeper’s ball”, but appreciating that the keeper may even be on his way in the first place. Equally, Alisson may have just left someone like van Dijk to clear the ball, but perhaps didn’t trust the new guy. Either way, it was an issue of inexperience within the defence, if not Kabak’s own personal experience as a footballer. He’s also playing alongside a player with about half a dozen games as a centre-back in his career.)

Indeed, as I wrote in both my recent books, team understanding – due to making fewer new signings (if you can get by with the players you have, because you’ve already shaped the ideal team and squad) – often actually increases team performance.

Liverpool didn’t sign a single first-team player last season, and won the league; and the only rookie minutes were handed out after the title was won. Adding more than one new player to a team is often counterproductive in the short term. Now, the Reds are already at almost 2,000 minutes of rookie minutes; from zero when it mattered, to 1,852 and counting. Add the 1,400+ league minutes of new signings, and it’s a mixture of inexperienced players and a lack of team cohesion.

The problem is that obviously at some point you have to introduce new players, or the team gets old and stale – but last season Liverpool were at a sweet spot, relying on previous signings who had settled in and were now all at a perfect age. There was no injury crisis; no relying on the kids. Even now, no one is “melting” – they’ve just suffered serious ligament damage from bad luck.

The bonus is that the minutes played by Jones and any of the other kids, including 20-year-old Kabak if he is retained, all count towards an expected improvement next season. Last season, Liverpool’s rivals were either able to (as they were out of contention for the league) or forced to play the kids. Now those kids are a year older, but not just a bit bigger and wiser, but now more experienced.

While Liverpool never intended this to be a transitional season – the age of the XI and the subs was still ideal – injuries have enforced one.

The good news is that, all being well, three of the world’s best centre-backs will be fit again next season (even if Matip won’t be fit all season). Diogo Jota will be back in the equation before then, and Thiago will be that bit more settled, and in addition to increasing his fitness and team understanding, will perhaps have learned to avoid sliding tackles. And then, players like Jones and Kabak may force their way into the team (or become go-to bench-men), rather than being used because of injuries to the main men.

Injuries Have Removed Goal Threat

Paul Tomkins: as well as losing a huge cutting edge at set-pieces – going from prolific to toothless – Liverpool have also lost at least three players who can score goals and add something in the final third.

The midfield is more goal-shy this season, and while the team was never built to rely on them for goals, the best goalscoring midfielders have missed most of the season.

Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain is a pro-rata double-figures midfielder goalscorer from open play (i.e. if he played all the minutes, he would be in double figures; instead, despite not playing every game, he got a healthy eight last season).

Indeed, prior to this season – when he has returned looking rusty and then low on confidence – he had played the equivalent of 39 full matches in the league and the Champions League for the Reds, and in those games, scored 12 open-play goals and made nine assists. (He’s also played in the domestic cups and scored goals.) Obviously he missed a year with serious injury, and then half of this season. He’s one of those players whose touch vanishes when out of form.

Naby Keita is another goalscoring and creative player. Virgil van Dijk adds five a season from centre-back, and Matip adds two or three, as well as the aforementioned effect they have on set-pieces in general.

And Diogo Jota has played 862 minutes in the two main competitions for Liverpool and scored nine goals, at a rate of one every 96 minutes. In other words, he’s arguably the most prolific minutes-based striker in the country this season. That’s far more prolific than Mo Salah on a per-90 minutes basis, and it’s without taking penalties.

He has scored goals against good teams (Atalanta, Arsenal, Leicester), and/or at important times in matches. If you look at the 22 players in the Premier League to have scored six or more goals (he has only five, so just misses the list of 22 published on the BBC), then the most prolific is Mo Salah, with a goal every 113 minutes (Ilkay Gündogan, out of nowhere, ranks 2nd of Jamie Vardy).

Obviously Salah also has half a dozen penalties, and while he takes them at an elite scoring rate, they bump up his figures in a way that they do not for Liverpool’s other strikers (who, in fairness, would probably miss a few).

Sadio Mané has often been electric this season, but he has scored a league goal only once every 255 minutes. Roberto Firmino has never been a rampant scorer, but he appears on the 22 top Premier League scorer list, albeit ranked 21st on minutes per goal (but ranks a healthier 11th from those players when it comes to just assists). So a fully sharp and in-form Ox has been missed, as someone who can take the ball forwards at pace and lash in a shot from 20 yards.

When asking for a few words on Oxlade-Chamberlain, Andrew Beasley supplied this regarding the Reds’ recruit from Arsenal:

“Re Oxlade-Chamberlain – the main loss has been his scoring from distance. Liverpool have only scored three goals from outside the box in league and Europe this season, and two of them were the 4th and 7th in the 7-0 at Palace. Only Gini Wijnaldum (second in 4-0) vs Wolves could be described as even vaguely important really. But Ox scored two of LFC’s three long-range goals in the Champions League last season (both at Genk), and one in the league too (the opener vs Southampton), plus one in the League Cup vs Arsenal if memory serves. Only Trent Alexander-Arnold scored as many in the two main comps, and his were all from free-kick situations. Ox was the open play long range king!”

I have always said that in the age of xG and sensible shooting – working the best positions, for the best chance of scoring – the long-range shot has to remain in the armoury; just as I say that players who love to cut inside must also go outside at least one in four times, even if they lose the ball, because it puts doubt in the defenders’ minds and then it makes cutting inside (the next time) a bit easier. You should never become predictable, and for a while, Mo Salah was becoming far too predictable – but ever since he scored his first goal of 2021 with his right foot at Old Trafford, he’s looked a far more balanced attacking player, and has scored six mostly excellent goals this calendar year.

Similarly, the long shot, while going out of fashion, remains a speciality. As Andrew says, someone like Oxlade-Chamberlain is perhaps the most potent player for this, and you can include his stunning goals against Manchester City in his first season. (Equally, City can score goals from outside the box, as well as walking it into the net.)

Unless it’s someone like Steven Gerrard, then by long-range I mean 20-25-yards, not 35. Teams need to know that you will at least try some shots, or defenders need not throw themselves into blocks. It’s handy against low-block teams, as the goalkeeper can be unsighted, and it can lead to spills, deflected goals, deflected assists (Virgil van Dijk against Everton when Origi scored in a famous Anfield derby), and to countless corners – albeit Liverpool still can’t do too much with them without all four outfield players who are taller than 6’1″.

The long shot, as Villa showed against Liverpool, can be a great provider of deflected goals. Indeed, Liverpool have scored just two deflected league goals in the past 18 months. Yet in the game against Villa, in that Black Swan of all Black Swan games, the Reds conceded three (and each was a massive deflection, and each went just inside the post or top corner).

The problem comes when teams resort to aimless long-shots in desperation, especially from players who never score goals. (When Dejan Lovren or Nathaniel Clyne would hit one from 40 yards I lose the will to live.)

Another issue is that Curtis Jones, at 20, has yet to chip in this season in the way that I feel he can. At the same age, after 50 games, Gerrard had scored just one solitary goal (versus Sheffield Wednesday), that was admittedly so good that you thought he’d become a goalscoring midfielder (and he did, eventually). Jones has a very healthy six goals in just 40 games, and half were against some good teams (Ajax, Everton and Aston Villa), but has only one in the league so far in his career. In a couple of years, that should start to have radically changed. Goalscoring often goes up a gear or two for players between the ages of 21 and 23.

While clearly injury prone, Naby Keita has started six league games this season. The Reds won five and lost the other (one of Adrian’s nightmares), to average 2.5 points per game, way above the figure in games where he didn’t start. The Reds never scored fewer than two goals in those games he started – which were against Leeds, Chelsea, Arsenal, Aston Villa, Leicester and Crystal Palace – and averaged almost four goals per game. Unlike in previous seasons he didn’t score or assist, but when he’s on a football pitch, things happen. When fit he’s a special talent, even if not everyone can see it.

While Liverpool cannot bank on Keita’s fitness, his absences – even to not have him as an option – are a kind of hamstringing of the team. While it may be that he just happened to start those six games this season when the team was on top form (in the opposite way to Thiago only returning to the team after months out after the Reds had already gone 150 minutes without a goal against West Brom and Newcastle), the fact that Liverpool have consistently done better when Keita is available remains a constant.

Andrew Beasley wrote this piece for TTT subscribers at the start of the season, about how much of an impact Keita has; although there is the couched optimism that the Guinean might have overcome his injury woes. (But at some point he still might – players can overcome such issues if the problem can be identified and rectified, even if not all players will.

At Keita’s age, İlkay Gündoğan had missed major tournaments with injuries and had never played more than 28 league games in seven seasons in the Bundesliga and one in the Premier League, where he only featured 10 times in his first season with City. Now he manages 50+ appearances a season in all competitions (although has just got injured again, when the league’s 2nd-top scorer). Indeed, Steven Gerrard had a lot of injury problems earlier in his career, as did Ryan Giggs. Yet those two had long and illustrious careers. So never write a player off, even if there are no miracle cures.)

I’ll quote a few bits from Andrew’s Keita article, but the whole piece is a strong argument for why, even now, we should not give up on Keita – but instead, find a way to figure out, if possible, how to keep him fit.

It can’t be an accident that Liverpool’s number eight performs well in so many different aspects of the game, not least as we know for a fact that the club’s head of research, Ian Graham, was hugely impressed by his numbers:

“What scouts saw when they watched Keita was a versatile midfielder. What Graham saw on his laptop was a phenomenon.”

It therefore seems worth pulling details from a host of recent articles and updating the figures to include the complete 2019/20 season to see what they tell us about Keïta. And if nothing else, if a central midfielder matches up pretty well to Kevin De Bruyne over the last two years [based on a data “radar”], then they must be on the right track.

… So what have we learned here? The data shows us that Naby Keïta is (somewhat on the sly) one of the key creative players in Klopp’s Liverpool team, be that teeing up a teammate with the final pass or putting someone else through to play the shot assist.

The former RB Leipzig man is also among the elite in Europe for carrying the ball around the pitch when he has it, and for attempting to win at back when he doesn’t. The net result? Liverpool’s record is better with him on the pitch than when he is absent.

[PT: and this obviously continues to be true this season.]

Defensive Errors

Andrew Beasley:

I’ve been thinking about the point I made above about defensive errors so I’ve done a little research.

Last season, Liverpool made 25. As they’ve made 12 so far in 2020/21, their rate per game has actually improved ever so slightly.

But only five led to a goal last season, whereas seven have this time around, so straight away there’s a bit more of a problem. Like anything in football, errors are not all equal – the one today was only ever going to end in a goal, rather than a shot, after all. Some are inevitably easier to get away with than others.

And look at the five which resulted in a goal last season, the scoreline in Liverpool’s favour at the time of the error, and the final result:

Southampton A, Adrián: 2-0 at the time, ended 2-1.

Brighton H, Adrián: 2-0, 2-1.

Watford A, Alexander-Arnold: 0-2, 0-3.

Arsenal A, van Dijk: 1-0, 1-2.

Arsenal A, Alisson: 1-1, 1-2.

38 matches played and only one game where a defensive error by Liverpool made any difference to the actual outcome. Even then, it occurred after the Reds had been confirmed as champions.

Now look at this season:

Leeds H, van Dijk: 2-1, 4-3

Arsenal H, Robertson: 0-0, 3-1

Aston Villa A, Adrián: 0-0, 2-7

Southampton A, Alexander-Arnold: 0-0, 0-1

Manchester City H, Alisson: 1-1, 1-4

Manchester City H, Alisson: 1-2, 1-4

Leicester City A, Kabak: 1-1, 1-3

Liverpool have lost six games so far this season, and they’ve gone behind to an error in four of those matches. Another instance was a penalty to Burnley (not an error in Opta terms, but clearly a defensive mistake), leaving the recent Brighton game, and that goal saw a failed clearance hit an attacker who knew very little about it.

It’s yet another issue this season where the small margins have absolutely gone against Liverpool. And when they’re on their 17th central defensive partnership of the season and the first choice goalkeeper has clearly got a few mental gremlins, I’m not sure what they can do about it. It will pass naturally, but it’s all part of the tailspin.

Top of the injuries table at present? Ouch.

Bottom of the VAR overturns table? Ugh.

Top of the table for errors leading to goals? Aha.

What an absolute clusterfuck. We were well in the game against City last weekend and unquestionably dominant here and then in the space of a couple of minutes one or two of the above factors have done for us in both matches.

We have unquestionably shot ourselves in the foot with the errors a few times recently – Southampton winner, go-behind goals to City and Leicester – and the Burnley penalty isn’t included in errors but proved costly too. But even a reasonable shake of luck, not even heavily in our favour, just our fair share and we’re having a completely different season.

And while our record for the season for converting clear-cut chances is pretty good, we’ve missed another two from two today. I honestly don’t believe there’s anything massively wrong with the team (though confidence is presumably shot to pieces right now) but all these things are adding to the drip, drip, drip of intolerable pressure. This is intolerable, Junior…

Defence Vs Attack

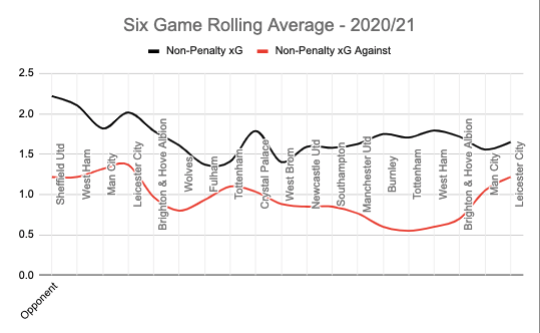

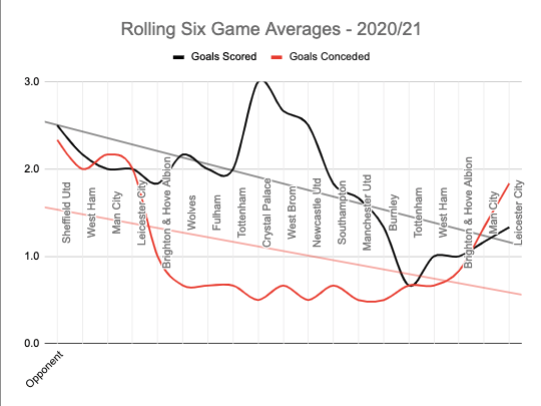

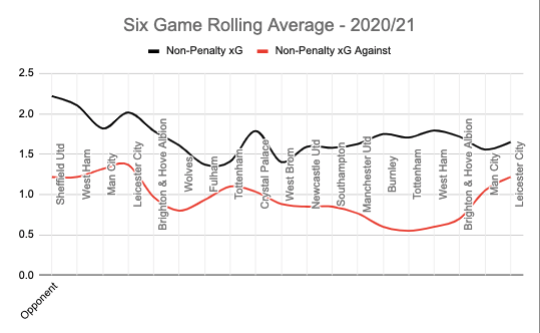

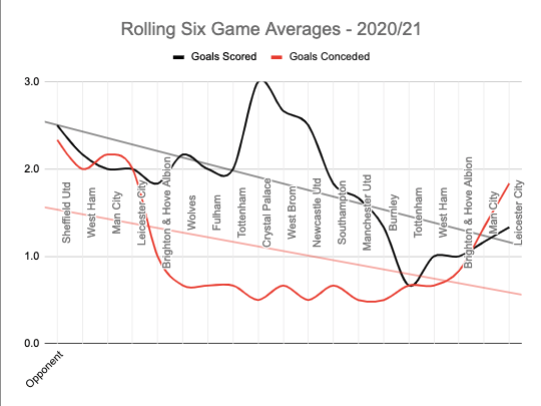

Daniel Rhodes: the three charts below showcase the Reds’ declining attacking prowess as the season unfolded (and several players remain out injured), and how the defensive side of the Reds’ game only really dipped – the opposition’s big chances rising again – since all of the centre-backs got injured, after a more stable period in January.

Once the Reds stopped scoring goals and entered that several-game drought, the pressure was applied to the defence; and by then it was lacking van Dijk, Gomez, Matip and even Fabinho.

Officiating: Refs and VAR

Chris Rowland: Ah, the elephant in the room. We need to talk about Kevin (Friend). And Anthony Taylor. And Martin, Andre, Mike, Jon, Lee, Paul and co.

Let’s be clear – there have always been complaints about refereeing. But let’s be equally clear – what has happened this season has been on an entirely different level to the usual carping about officiating fortune.

Paul Tomkins: It’s never easy arguing that you’re being screwed by the refs (and the VAR) but there’s a shit-ton of neutral data that suggests that, this year at least, the Reds are being jolly-well rogered.

Chris Rowland: This is a subject that’s so complex and, this season at least, full of so many contentious and downright insane decisions, we will be covering it separately, in great depth, next week, including subscriber Vinnylfc‘s gargantuan effort in trawling through all this season’s TTT match threads (league games only, up to and including Leicester away on February 13th) to produce a deep, game-by-game dive into Liverpool’s troubled relationship with refs, screens and some folk concocting strange artificial lines on the pitch in the back of a van somewhere near Stockley Park.

For now, here are a few bits of information on where we are this season:

– the official stats on VAR overturns this season; anyone who calls Liverpool LiVARpool after this is officially and just plain wrong!

– Planet Football’s version of the latest VAR figures.

– A list of 16 refereeing decisions that went against Liverpool this season up till Jan 6th; there have been plenty more since.

–A video looking at various poor decisions Liverpool have had. It isn’t comprehensive, and we know other teams have had some shocking decisions this season too – but the totality of evidence suggests the Reds have had the worst of it, bar far. Even compared only against Liverpool’s previous seasons, it’s been a radical outlier. Often these decisions have been at vital points in matches: when the scores were close, and not when either Liverpool or the opposition were already well ahead.

Paul Tomkins: Plus, Liverpool have won a healthy six penalties this season, albeit plenty of other clubs have won more in a season where the numbers have increased across the board; but a scarcely believable eight have been given against Klopp’s men. Half of these were stonewallers, but the other half were iffy at best. Thankfully some have been missed, but it’s still cost the Reds points, and is already 8x the number conceded in the league last season. Perhaps Liverpool got lucky in conceding just one in 2019/20, although the first-choice defenders obviously defended better than the stand-ins this season. Even so, to concede one league penalty every three games is bonkers.

Until Next Week…

For now we’ll end there, and if we think of any other issues we may update the piece.

But now we’ll go away and flesh out the analysis of the officiating madness that has been 2020/21…

See below for details on how to sign up to TTT to join in the intelligent debate and to read paywalled articles – something we’ve been doing for 12 years, to keep the site’s hosting and staffing costs covered and to enable us to provide free content like this.

Paul Tomkins

The creator of this website; author of several books on Liverpool FC, and of one novel. Co-creator of The Transfer Price Index (TPI). Columnist on the official Liverpool FC website between 2005-2010. International man of mystery. Possibly bald.

I’ve shown that we’ve scored one set-piece goal in 16 games without the Reds’ biggest two centre-backs, having averaged a 1-in-3 when both were in the team, and 1-in-4 when it was just Matip and no van Dijk. (Since I created the graph, it’s now one set-piece goal in 18 games without both van Dijk and Matip – pro rata, that’s the equivalent of just two set-piece league goals per season, when last season the Reds scored twenty. The effect on the goals column is the same as replacing Mo Salah with an ageing Rickie Lambert or a disinterested Mario Balotelli.)

I’ve shown that we’ve scored one set-piece goal in 16 games without the Reds’ biggest two centre-backs, having averaged a 1-in-3 when both were in the team, and 1-in-4 when it was just Matip and no van Dijk. (Since I created the graph, it’s now one set-piece goal in 18 games without both van Dijk and Matip – pro rata, that’s the equivalent of just two set-piece league goals per season, when last season the Reds scored twenty. The effect on the goals column is the same as replacing Mo Salah with an ageing Rickie Lambert or a disinterested Mario Balotelli.)