The “Black Swan”: that event so freakishly rare you rarely see them.

As I’ve noted throughout the season, pretty much the only swans seen at Liverpool Football Club in 2020/21 were of the jet-black variety (with all the sheep mysteriously that variety too). In this bizarro world, perhaps there has been a proliferation of white widow spiders, white crows and white jaguars; and of course, throw in some pink giraffes and green elephants, just to make it all the more trippy.

I had been preparing to point out how these Black Swans killed Liverpool’s Champions League qualification hopes, and yet despite more setbacks than you’d probably expect in 20 seasons, the Reds clawed their way back from the brink of mid-table, to finish 3rd. They did so minus all their senior centre-backs – fielding their 7th and 8th choices – and their leader and captain, amongst other absentees in the run-in; having had long-term injuries to various other players.

It will never be Jürgen Klopp’s most celebrated achievement, but it could be his most impressive.

Indeed, as the corpses of Black Swans littered the Anfield area in this era of plague and pestilence, we got to see something even rarer: a flying Golden Griffin, complete with gloved talons, as Alisson Becker channeled his inner mythic beast to head home the goal that potentially earned the Reds in excess of £50m and, more importantly, the cachet of elite football – and most vital of all, the chance to win next year’s Champions League (or, to at least enjoy some big Anfield nights that transcend the “ropey” league).

The Golden Griffin swooped, and for the first time in nearly 6,000 games of football in Liverpool’s history, and perhaps getting close to 100,000 top-flight games in England since the inception of league football in Victorian times, a goalkeeper scored the winning goal in a game (as well as, I believe, becoming the first to score at that level with a header – most of them have been long clearances that caught the wind).

In that moment the last living Black Swans fell from the sky, dropping dead to the ground.

Diagnosing Disaster

Working out what was going wrong – in a football sense – in a season when so many factors were having an influence was almost impossible. I compared it to trying to diagnose one specific illness from an inexhaustible list of symptoms.

People would pick one simplistic (and often incorrect) thing and focus on it: “Thiago slows Liverpool down”.

Yet this didn’t explain why, during the midseason slump, the Reds were still creating good chances from open play – just a) missing them (was that Thiago’s fault?); but b) no longer creating them from set-pieces (and he neither took the corners, nor was expected to be on the end of them).

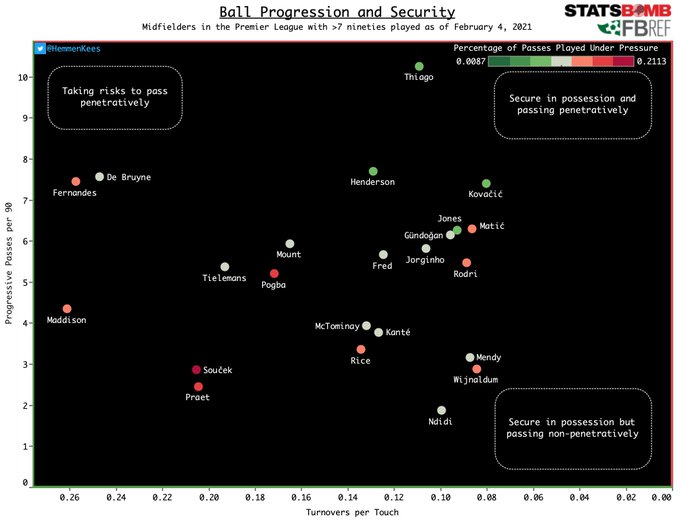

This is an image from a few months ago, at the peak of the “Thiago slows Liverpool down” nonsense. You can barely see his name, as he’s almost literally off the top of the chart.

They saw the addition of Thiago coinciding with the slump, but didn’t note the loss of the third and final major centre-back as a far more decisive moment; especially at a time when Nat Phillips and Rhys Williams had one Premier League start between them. At that point, Liverpool were top of the league.

Both came into the side and had harrowing games that perhaps suggested they were not ready for the deep end; but while they appeared to be drowning, they were simply learning to swim in public. Fabinho (and even Jordan Henderson) at centre-half made sense in that the others did not appear ready; Ozan Kabak, who arrived in an emergency deal, was himself only 20, and he had to get up to pace with the Premier League with zero time to adjust. (He did very well considering, even if he didn’t quite convince the higher-ups at Liverpool that he was ready for a permanent deal.)

Thiago had his ups and downs this season, after returning from open-knee surgery performed by a snarling Brazilian, but slowing Liverpool down was never true. He made too many fouls, and at times his lack of pace (and fitness after injury) caused optical alarm (he appeared to be too sluggish), but he always made the ball do more forward-thinking work than any other midfielder in the country. And as the season progressed, he increasingly bossed games. Vitally, he was able to have a bodyguard in Fabinho – although he continued to battle for the ball and win a surprising number of headers.

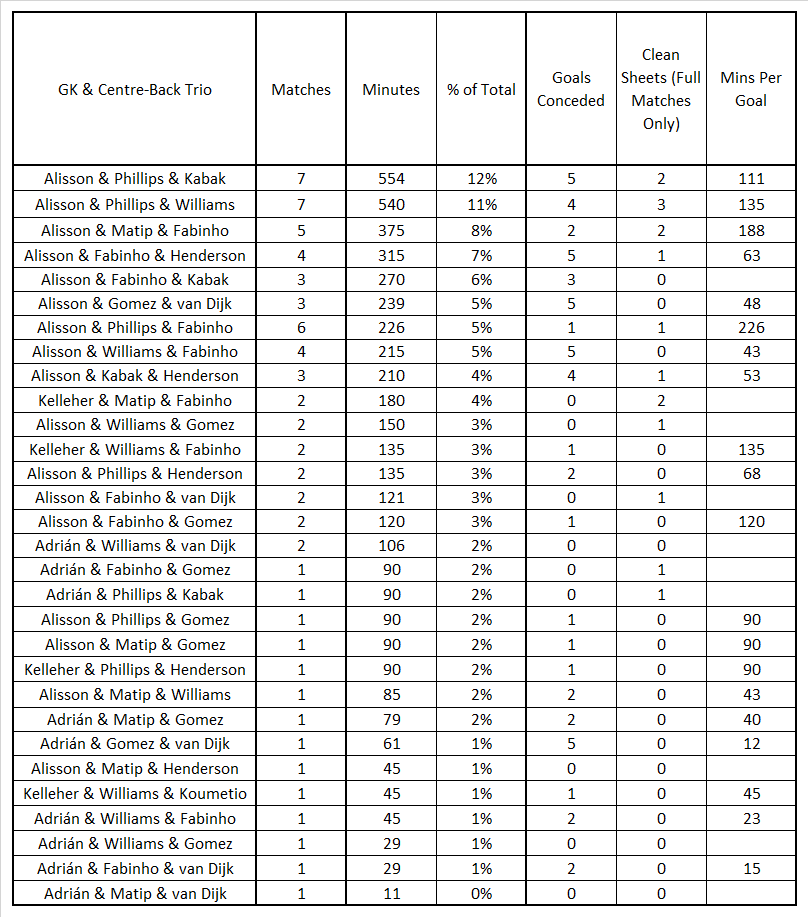

Such an explanation – Thiago was the problem – ignored that lack of stability at the other end, with a different goalkeeper and centre-back pairing almost every game. Liverpool used twenty different centre-back pairings, and thirty different rearguard trios (GK-CB-CB).

Such narratives ignored ten or twenty other important factors.

They ignored that injuries to the two main goalscoring midfielders from open play: Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain and Naby Keïta; the two who would run ahead of the strikers.

That pair also happen to be elite pressers, too (Keïta remains the best at the club, but he needs to get an injury specialist to sort him out. He remains a fantastic player, but at this stage cannot be relied upon. I wouldn’t write him off, but I wouldn’t bank on him either. My view is that you try to limit the churn in the transfer market, and work on getting talented fringe players to challenge for starting berths; as seen at Manchester City this season, with İlkay Gündoğan, John Stones and João Cancelo, amongst others whose form completely switched this season).

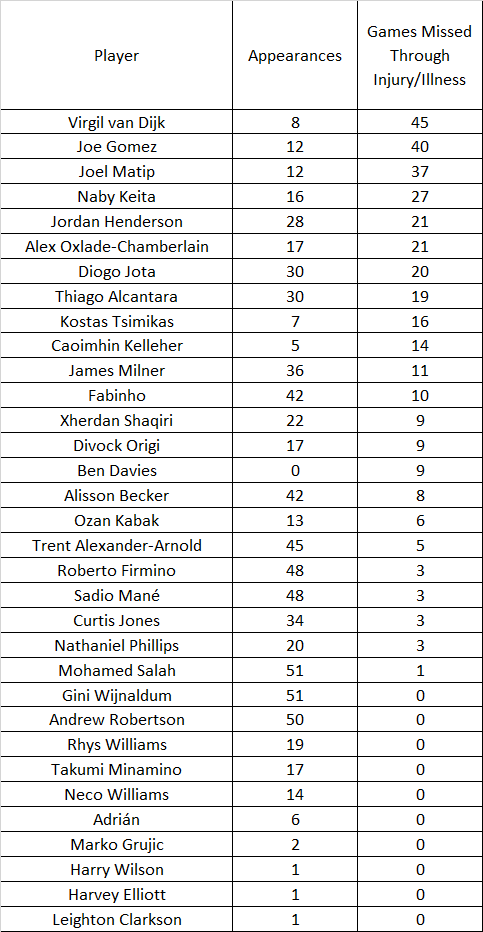

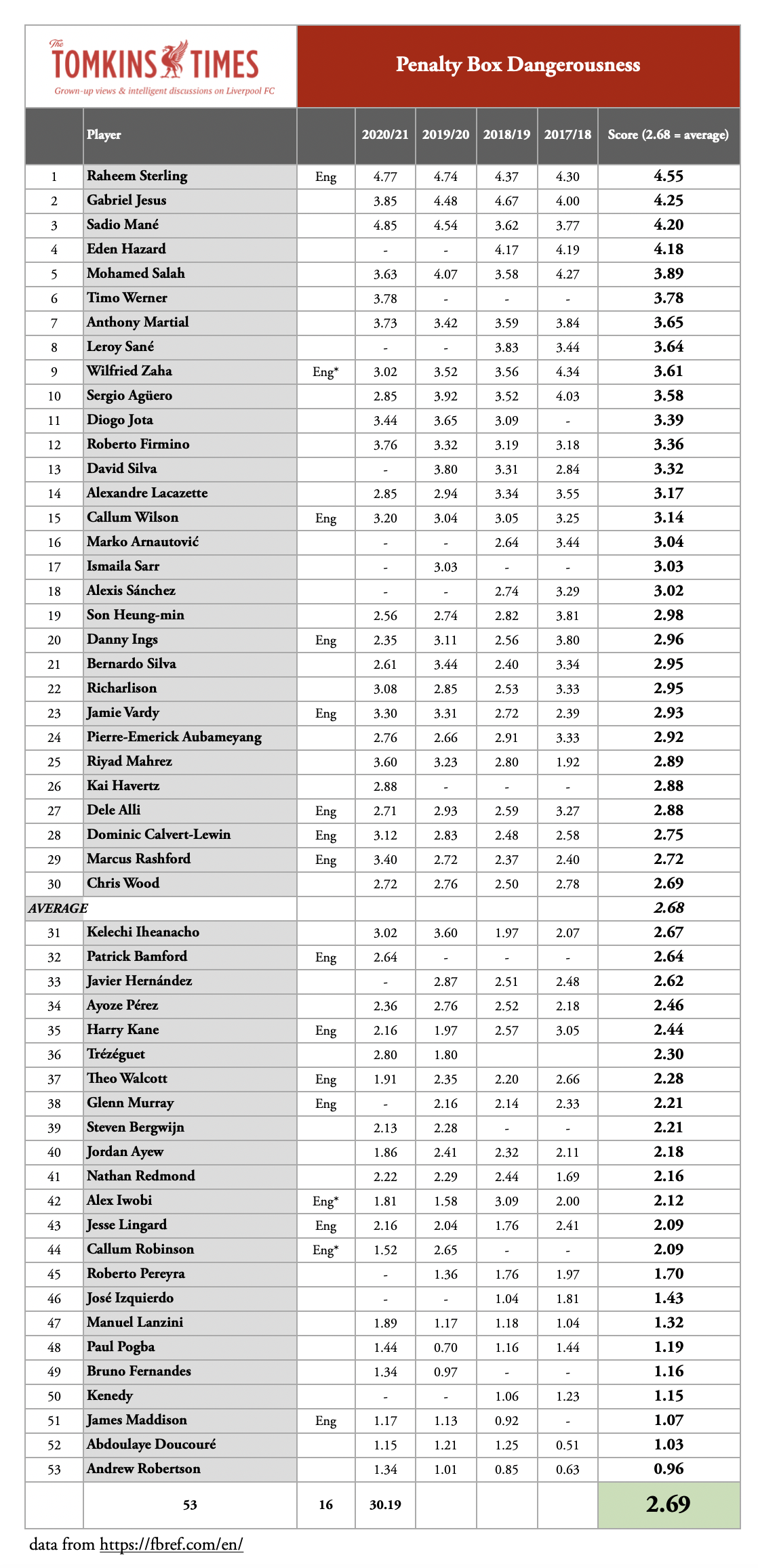

Another elite presser was Diogo Jota, the league’s best marksman in terms of shots on target per game, who missed three months. Indeed, Liverpool had just two games where a total of four serious long-term knee injuries were sustained. These two games alone cost Liverpool c.100 appearances (from Virgil van Dijk, Thiago, Jota and Tsimikas: three major players, and one much-needed backup).

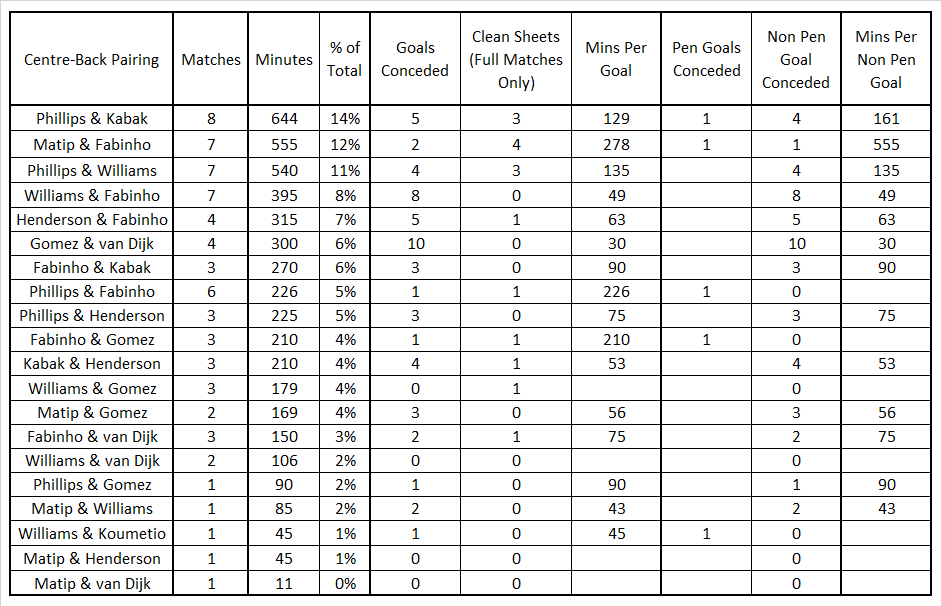

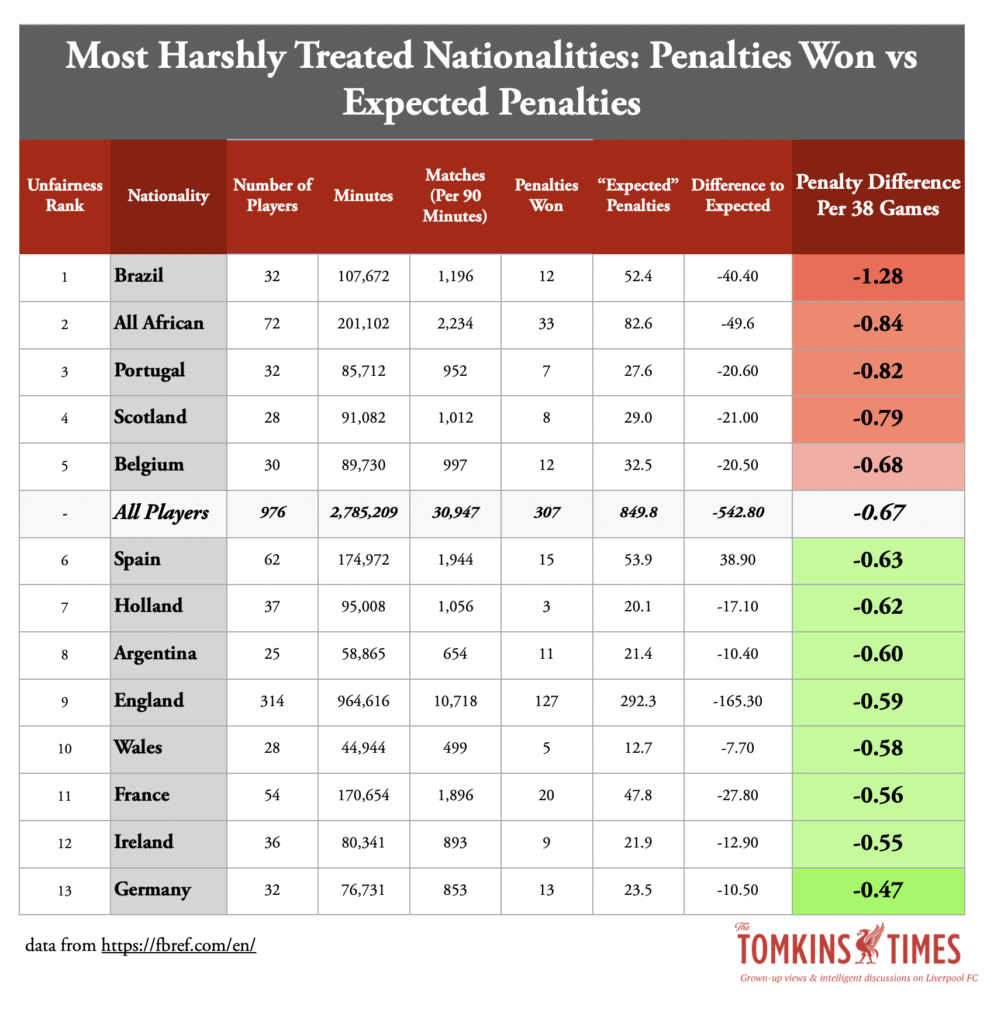

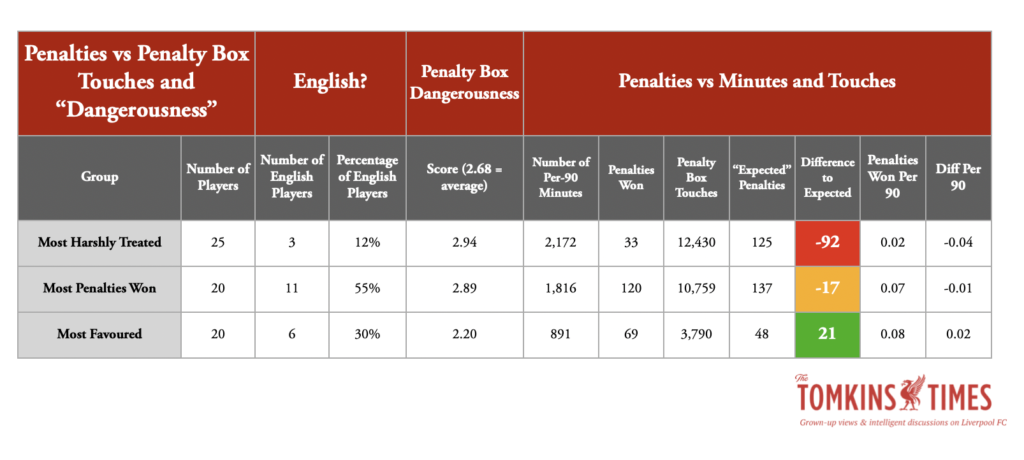

The narrative ignored how Liverpool were not being given penalties (an ongoing trend), but were conceding them at an unusually high rate (a new trend). Despite doing two thirds of the attacking, the Reds conceded more penalties than they won.

The four teams vying with Liverpool for the top four each won between 9-12 league penalties, ranking #1-4. Liverpool ranked joint 7th, level with several other clubs, to mean that every single season has seen Klopp rank lower on penalties won than league position (as did Rafa Benítez), while every single season in the top flight has seen Brendan Rodgers rank higher in penalties won than league finish.

While that may be merely coincidental in Rodgers’ case, there is this very weird pattern where not only do British players get favoured in both boxes by referees (based on in-depth studies we’ve undertaken), but the teams of British managers seem to fare much better too – it certainly applies to Liverpool: Benítez, lower every year; Rodgers, higher every year (ditto Dalglish and Hodgson); Klopp, lower every year.

(The absolutely scandalous diving by Jamie Vardy explains some of this recent trend: the most egregious one I’ve ever seen was how he grabbed Davison Sanchez’s arm and then threw himself to the ground. What next? Vardy to get hold of a centre-back’s hand and thrust it into his face, to pretend he’s just been punched? All teams have players who go down easily, but this is some new-level conniving, that the VAR inexplicably failed to recognise, when all neutrals could see it a mile off.)

For the second season running a relegated team won more penalties than Liverpool, who had the best attacking xG figures in the top division.

Again, this makes no logical sense. (And no opposition player has been sent off at Anfield for several years now; Jordan Ayew continued the trend of players staying on despite at least two bookable offences.)

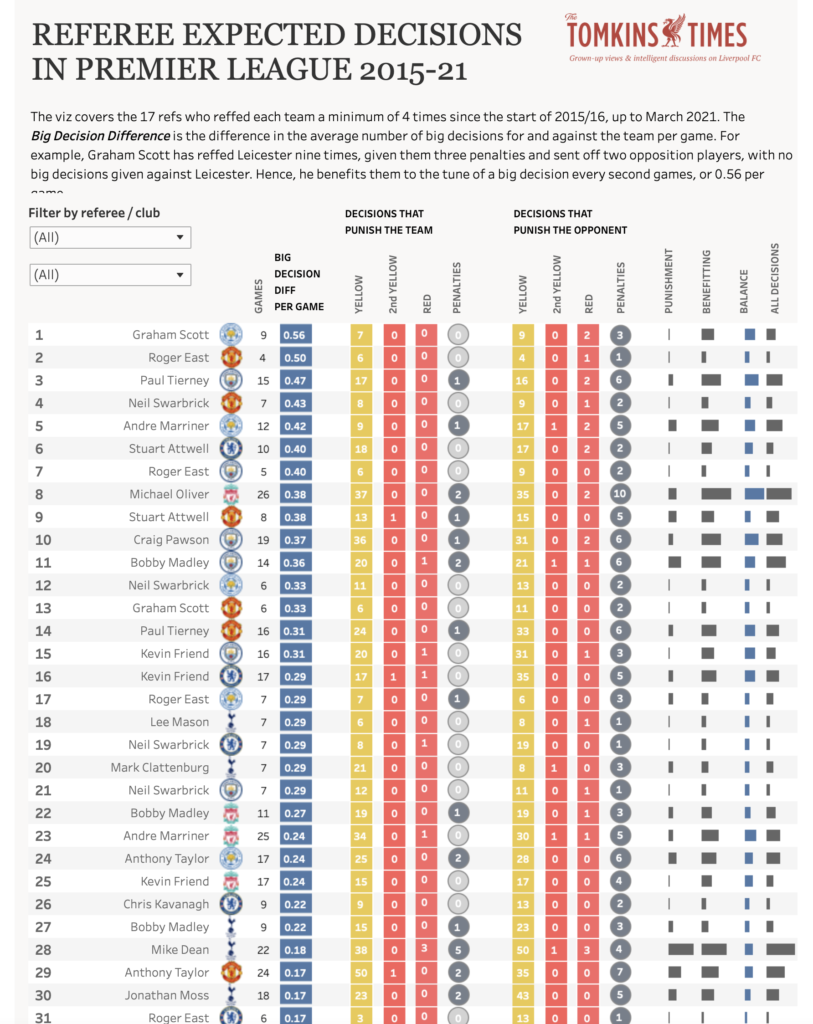

One thing we studied on this site was how officials from the north-west show a clear bias against Liverpool, and that the closer to Liverpool their hometown, the more biased they are; as if it’s a bend-over-backwards bias that is so prevalent in modern society (trying too hard to look unbiased, as the optics are all the counts).

With subscriber “CVT” and old friend Rob Radburn, we created this interactive chart (click this link for the longer and fully interactive version):

As you will see from the full version, the three least generous refs are all examples of officiating Liverpool matches, and most referees – when it comes to their treatment of Liverpool – rank towards the foot of the table. The only active referee who is even remotely generous to Liverpool is Michael Oliver, whilst the older the refs are (and the more north-west their place of origin), the worse things get on average.

(Note: data was correct up to March, and as such, no further penalties or red cards were awarded in Liverpool’s favour. In fairness, Anthony Taylor did award one, but Paul Tierney overruled it.)

This overly harsh treatment by north-west refs would explain why, in a season when north-west refs did most of their games due to Covid-19, the officiating got even more punishing. While we must all be aware of our own biases (mine are pretty clear!), we must also be aware of bias overcorrections, which are about appeasing the masses, and not being honest. We have to correct for our biasses, but not overcorrect to look virtuous and just.

Outrage on social media leads to a lot of accusations of bias in all areas of life (and sport), and so people veer towards anti-bias virtue signalling. People will accuse Mike Dean of favouring Liverpool, yet he remains a nightmare for the Reds in terms of big decision balance (excluding VAR interventions). Dean gives tons of penalties, but he’s given none for Liverpool, and two against (one was outside the box, but he gave the foul).

My aim has always been to mine the data, not work on raw emotion (although I also tweet some absolute horseshit in times of high stress, which, along with the toxic nature of social media in general, is part of the reason why I try to avoid those places these days. It thrives on our worst instincts).

Anthony Taylor, from Manchester, has bottled some big decisions for Liverpool (most famously at Man City in 2019), but has awarded the Reds a healthy six penalties, albeit with one overturned by the VAR from Wigan. While we may recall the Vincent Kompany assault on Salah that only resulted in a yellow card (and helped tip the title in City’s favour) and think he’s biased against Liverpool, he’s actually a fair ref, according to the data. Again, the optics are what we remember – the high-profile events. The data is what reveals the bigger picture.

I would put Taylor with Oliver and Andre Marriner as the only three refs who are even vaguely fair to Liverpool. (The Premier League and the PGMOL may be aware of which referees favour which teams when appointing them. It certainly felt like they were trying to handicap Liverpool this season, to the point where favourable refs were replaced at the last moment by unfavourable refs in the run-in. That’s not to say it’s a conspiracy, just that I wouldn’t necessarily trust either the Premier League or the PGMOL, with their rampant self-interests.)

Liverpool had to dig themselves out of a hole without a single penalty after early February, which was itself the only penalty since December 13th, as refs and VARs otherwise dished them out left, right and centre. As ever, Michael Oliver was the only referee who gave Liverpool a vaguely logical number of penalties, based on the data. He gave the Reds three this season, and all were correct decisions; no other ref gave more than one.

The simplistic narratives ignored the lack of a home crowd, which turned Liverpool’s best-ever home record (four years without defeat, which still applies if you exclude three-quarters of a season in an empty stadium) into the club’s worst-ever run, in a season which – for the first ever time across the whole top flight – saw more away wins than home wins. Burnley also suffered their worst ever home run, and Everton and Manchester United had their worst home runs for many, many decades. Manchester City won the league, and lost a fairly hefty four of 19 games at home; yet adding together the previous three title winners (Liverpool, City and City) saw just two home defeats in 57 league games in those three seasons. So, the lack of crowd was clearly a big factor too.

Simple one-fact narratives don’t even cover the way the Reds’ preseason – already truncated – was thrown into chaos by last-minute changes to the training camp location due to Covid issues. They do not cover the lack of fitness in the squad as a result, and how, with up to a dozen injuries at a time, rotation was harder; and therefore fatigue in the middle of the campaign became an issue for some players in a more heavily-packed schedule.

Andy Robertson desperately needed cover, but his cover got Covid and then a serious knee injury; and when his cover was fit again, Klopp essentially admitted he couldn’t really change much of the core of the team, due to the ever-changing centre-back pairings. The manager could have given more minutes to Kostas Tsimikas had it not been two rookie centre-halves, who needed Robertson’s know-how alongside them, and a settled midfield ahead of them.

Robertson was clearly knackered, but normal rotation was out, as Klopp strove for stability. And he was proven correct to do so, albeit in a gamble that could have gone either way (as is the case with all judgement calls).

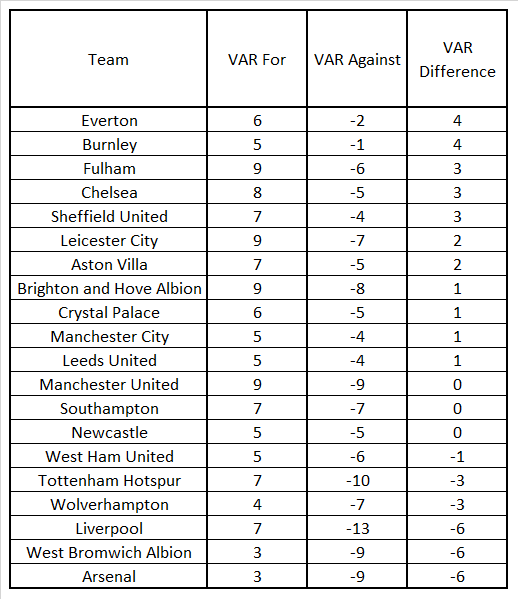

The simple narratives do not include the insane balance of VAR calls that went against the Reds, mainly in the periods when the team was struggling. Seven decisions went in their favour, but a whopping thirteen went against. Of these 13, some were as clear as day – but about half were scarcely believable.

I’m not being wise after the event. I have been tracking these things all season on TTT, with the help of Andrew Beasley, Daniel Rhodes and others. This has been a shocking outlier of a season, and the notion that these were Mentality Midgets and not Mentality Monsters has been disproved beyond all doubt.

The Biggest Factor

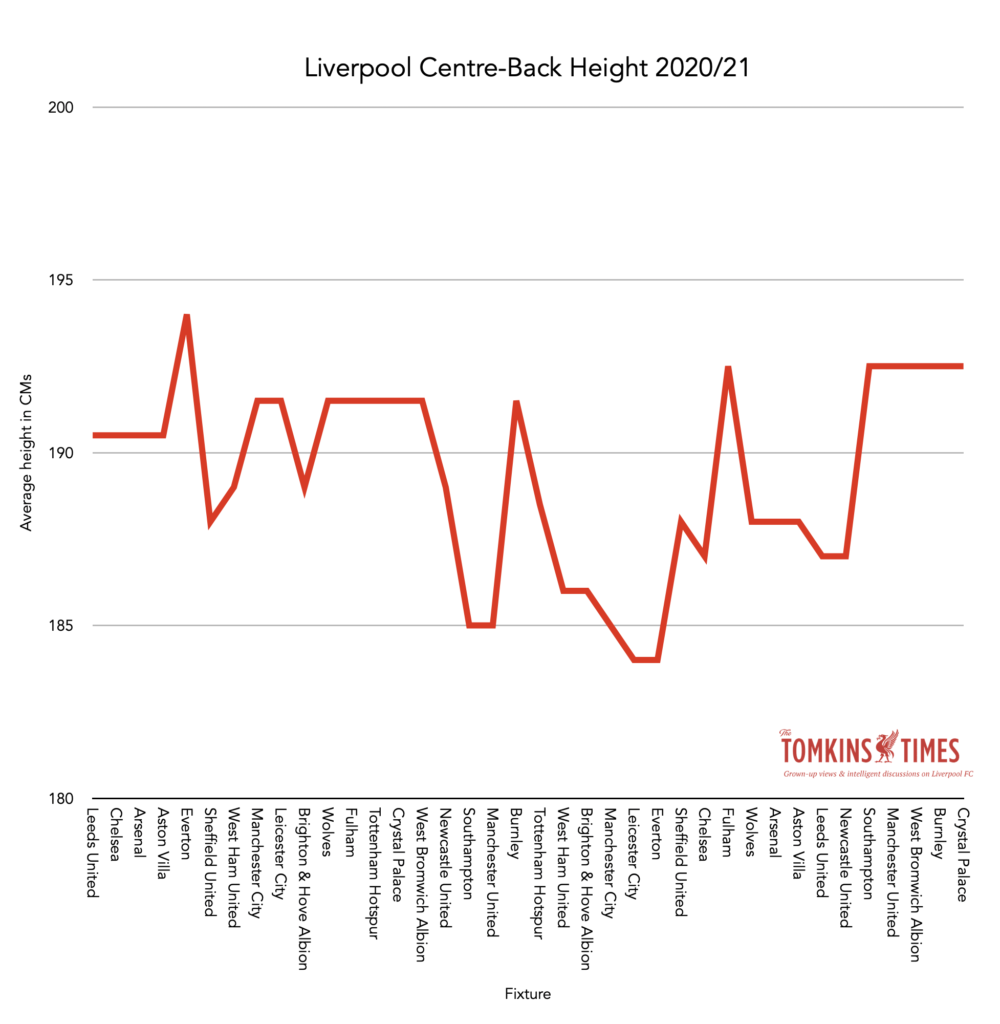

But if I had to pick one single factor – or rather, the biggest contributing factor – then aside from often lacking so many world-class players (whose value often exceeded £300m, which meant the Reds had more financial investment in the treatment room than on the pitch), I’d say that a lack of height (itself due to those injuries) was killing the Reds.

Possession stats had not changed much, open-play xG stats had not changed much, referees were still not giving Liverpool many penalties, but set-pieces at both ends (and an inability to win headers in the middle of the park) were – to my mind – behind the slump against big-bastard teams.

They just happened to be the “smaller” clubs, which incorrectly implied that the Reds just weren’t up for it; but these little clubs had the tall, bodybuilder players that overpowered Liverpool’s technicians in the absence of the Reds’ enforcers (and fair refereeing).

They played aerial percentage football that was Liverpool’s Achilles heel (if only there was an Achilles head). These alehouse units played the kind of football that Joel Matip, Virgil van Dijk and Fabinho (as a midfielder) were brought in to combat.

The most simple are startling statistic I can find is the disparity between when Liverpool – overall the shortest team in the league this season (and by an even greater margin when you look only at outfield players) – were at their smallest, and when they were at their tallest (which wasn’t even within an inch of the average of the tallest side, Manchester United).

“Shortest Liverpool” had relegation form, over a run of 13 games. PPG: 0.8, or 29.2 for the season. Or, the same as Fulham.

“Taller Liverpool” had league-winning form, over a run of 25 games. PPG: 2.3, or 89.7 for the season. Or, better than Manchester City.

It’s that simple. (Even if it’s not really that simple, as nothing ever is.)

But the stats really are that startling.

(Another thing: Man City added height to their team this season, and fielded taller centre-backs than last season, and Rodri won an absolute ton of headers, to rank 4th in the entire division, while John Stones has improved in the air with age and experience, and ranked in the top 10.)

However, which Premier League player ended the season winning the most aerial duels as a percentage? Rhys Williams.

Which player’s inclusion in the team suddenly increased the set-ball threat at the other end? Rhys Williams.

Nat Phillips, four years his senior, is clearly more aggressive, and goes for less-winnable duels, and helps in this regard too, as he’s in the top 75 percentile for centre-backs; but Williams is just bloody tall.

Williams won over 82% of his duels, and he contested almost 40. That is an elite figure, and the only player I’ve seen better it in recent years is Joel Matip, with 90% last season (from 46 duels).

Who ranked 2nd last season? Virgil van Dijk, at 80%. Who ranked 1st the season before? Virgil van Dijk.

As good – and honest – as Ozan Kabak has been, he’s just 6’1″. He won just 55% of his aerial duels this season, and whilst Fabinho is good in the air for a midfield (in that he’s tall for a midfielder), he’s substandard in the air as a centre-back. (Indeed, he doesn’t even go up for corners anymore.)

Most young players improve in aerial duels as they get more experienced and beef up a bit. Their timing improves, their ability to use their body improves, and they gain power from the gym. But height seems key. (Note: as ever, set-piece goals exclude penalties.)

Williams was also standing right next to Roberto Firmino in December when the Brazilian headed that remarkable winner against Spurs. That was the last set-piece goal the Reds would score until Williams returned to the side for the final five league games.

The Reds won all five, and scored their first set-piece goal for five months. Coincidence?

They also scored their 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th and 6th set-piece goals since the game after that Spurs fixture back in 2020.

Coincidence?

This was after an admittedly Black Swan run of no set-piece goals for five months. There was one more set-piece goal after Firmino’s against Spurs in December: the next game, when Mo Salah headed home. This was also Matip’s last full game, and Matip – 6’5″ – headed the assist, before he got injured again in the next game at West Brom (when Liverpool threw away a 1-0 lead after his exit, and the slump started).

According to Andrew Beasley, between Salah’s goal against Crystal Palace and Diogo Jota’s at Old Trafford, there was a gap of 2,383 minutes and 91 set-piece shots without a goal, across a shit-ton (my technical term) of free-kicks and 183 corners. The quality of the balls into the box wasn’t necessarily different, as both full-backs played all these games – albeit after Covid and injuries, Trent Alexander-Arnold was looking sluggish. The balls were whipped into the danger areas, and Liverpool had no height to contest them. Smaller players can score from set-pieces, but rarely if the opposition’s tallest players have no tall players to mark, so mark them instead.

That five-month drought saw Liverpool field mostly shorter centre-back pairings, and that meant an increase in set-piece goals conceded, too. The dip in height correlates directly with the slump in results, albeit height won’t have been the only factor; it just feels like the main factor to me.

While I haven’t done so, if you overlaid the league table, it might look quite similar! The Reds started the season as the best team (and were top until all the senior centre-backs fell to injury), and ended the season as the best team.

As I said, surely other factors applied, including that the stand-in centre-backs were not always specialist centre-backs (and when the average was lower earlier in the season it was with the elite-paced Joe Gomez, 6’2″), but from the ten league games where the Reds fielded centre-backs who averaged below 188cms in height, they took just 0.6 points per game, with just one win: against West Ham away. Centre-back pairings 188cm or taller resulted in title-winning form.

Now, I admit that this is an area of fascination for me, but I’m not cherry-picking the data.

For many years I’ve been talking about the importance of aerial duels in English football. I started focussing on it in 2015, when the Reds were the smallest team, and the worst in the air by some distance.

It’s even more important if your strikers and midfielders are superb but small. You wouldn’t swap Mo Salah for Ashley Barnes because one is a giant bodybuilder and the other is 5’9″, but if over 30% of goals are from set-pieces, then you end up essentially gifting results to the opposition if you cannot compete on them. Brendan Rodgers tried to add height in Christian Benteke, but it was at the expense of quality. (Benteke was excellent at Aston Villa until he suffered a serious injury that robbed him of pace.)

Remember, Liverpool’s 13 shortest starting XIs in 2020/21 scored zero set-piece goals, and conceded five, and had relegation-form results.

You don’t need a tall team per se, but you need four or five tall players to handle the aerial onslaughts. This is why Man City bought Rodri, and Stones scored four goals as well as improving defensively. In the last two seasons they have bought several players who are 6ft or taller.

Rhys Williams – as tall as Joel Matip, and aged just 19 until fairly recently – started seven Premier League games, and the Reds won six of them. The Reds scored a staggering c.60% of their set-piece goals in these seven games (and the other 40% came via goals or assists by van Dijk and Matip). The age of 19/20 is an absolute baby for centre-backs, where almost all players (especially what I call Slow Giants) start to look the part at 24/25.

Williams and Phillips both clearly lack pace, and both lack experience. Both are Slow Giants, and the last thing you want is to pair a Slow Giant with a Slow Giant. So how did they succeed? It seems that Liverpool had enough quality, just not enough height. Ozan Kabak and Fabinho are quicker than both, yet it seemed that height was the missing factor.

While Phillips seems to be the chaos-monster, Williams is the unmarkable object. Phillips’ aggression helps, without doubt. He’s the one that goes looking for the duels, and will head a 50-50 even if the ball is on the ground. But Williams is just a giant, and one who will surely only improve in the air with time spent on the pitch (and in the weights room). I was lucky enough to be at Anfield on Sunday, and I really appreciated his composure and touch, as well as how he caused chaos in the Crystal Palace area (and Palace are one of the league’s tallest teams, as well as being its oldest. You can count on Roy Hodgson bequeathing a team aged 30 to his successor, time after time).

Incredibly, Roberto Firmino has now outscored Virgil van Dijk from set-pieces since the summer of 2018, albeit van Dijk has played only two full seasons in that time.

But Firmino cannot score from set-pieces without a giant or two to act as distractions. It doesn’t even need an elite aerial threat like van Dijk; it just needs some bloody tall kid, to get in the mix. Being 6’4″ or 6’5″ makes a huge difference to aerial win percentages, and it makes flick-ons at corners all the more likely. Years ago I worked out that the best aerial win percentages belong, on average, to the very tallest players (if you group them by height), and they fall in line with every inch lost in height.

Peter Crouch was not a wonderful technical header of the ball, nor could he jump that high. But he was (and presumably still is) 6’7″, and thus scored the most headed goals in the modern era.

When Firmino headed home the diagonal free-kick against Man United a few weeks ago, Williams was initially standing right next to him, taking up the attention of three tall United players, despite the fact that Williams has no clear aerial ability in terms of heading at goal (as we saw when unmarked this weekend). Three men on (or near) Williams left one player (Paul Pogba) half-marking Firmino at the far post as he stole a march.

Below is Firmino heading home against Spurs, with Williams (ducking) helping him to create a two-on-one.

When Liverpool broke through against Palace at the weekend, it was Williams heading the ball on to Firmino after getting above the tall Cheikhou Kouyaté; perhaps by accident, but there they were again, the same pair linking up. Kouyaté failed to jump, and tried to foul Williams, to no avail. He did stop Williams from heading at goal, but the ball fell to Firmino.

Williams was involved in the set-piece goal against United – before Firmino’s – that broke the five-month drought. He was the one who was challenged by David de Gea and not one but two United defenders, which meant space for other players. Three United players against Williams, and the ball fell to Mo Salah in space in the box.

Williams also helped win the penalty from a corner that was bizarrely overruled (yes, Eric Bailly won the ball, but it was not won cleanly, and the follow-through was extreme – far more of a penalty than Fabinho’s challenge outside the box against Sheffield United!).

At 0-0 at Burnley, Williams headed down from a corner and Phillips somehow volleyed over. It was a golden chance. Williams didn’t even need to jump.

When Mané set up the vital second goal in that game, from a 2nd-phase corner, he lofted the cross directly over Williams’ head at the near post, as the Reds’ no.46 stood surrounded by Burnley players; in snuck an unmarked Phillips to finally show that he can be a threat in the opposition box too, after various wild attempts.

All this is under the radar, with Phillips and Mané getting the plaudits; yet Williams is taking up the attentions of half the home team. You could argue, via the image below, that five players are stationed to deal with Williams, and just one (Ben Mee) has to mark both Phillips and Firmino, as well as being one of the five in a position to challenge Williams (whilst Salah lurks at the back post too).

And when Williams went off late-on against West Brom, it was the Reds’ 6’4″ keeper, challenging for the ball along with the aggressive Reds’ 6’3″ heading-machine, that won the game and essentially banished the Black Swans. There was a height overload at the back post, and it turned Liverpool’s fortunes around, and gave us the best moment of the season by far.

While delivery is obviously important, height is absolutely vital at attacking set-pieces – and sometimes it can be the goalkeeper, too. It’s similar to how a quick striker often just needs a half-decent through-ball and he can turn it into a killer pass: a tall player doesn’t necessarily need the perfect cross.

It’s hard to quantify how much better Thiago did with “bodyguards”, but he started the season looking sublime in a team containing van Dijk, Fabinho and Henderson, and then had a slump in a short-arsed midfield, with issues at centre-back.

One other issue during the slump was just how bad the Reds’ finishing was, but this was also partly linked to height and set-pieces. Remember, Firmino gets a lot of his goals as the free man when taller Liverpool players are being marked. He’s the one that finds the space. A lack of set-piece goals put more pressure on the strikers, and for a while they were weighed down. At the other end, the Reds conceded from set-pieces, and conceded penalties that cost a lot of points.

The law of averages suggested Liverpool’s fortunes in front of goal would change, and they did. Sometimes you just have to ride out the storm. Next season, Liverpool should have elite tall players back in the team, as well as (hopefully) other players being fit again. But now, the Reds also have Williams and Phillips, two rookies who helped transform the season. The worst season in a decade turned into one of the best run-ins, and in the absence of up to a dozen players at a time, new heroes were born.

Part Two

Some crazy Black Swan stats, many compiled by Andrew Beasley, often at my request.

Injuries

![]()

Defensive Chaos

Penalties Won

Officiating and VAR

Quick Officiating Lowlights Reel via Twitter

(Complete with terrible music)

https://twitter.com/lverpull/status/1396792221559558147?s=21

Summary

The Golden Griffin killed all the Black Swans.

The end.

So, do English players “dive” or fall differently? My sense is that players like Harry Kane have mastered the plank-like flop (see the image to last week’s piece), where there’s such an attempt to not arch the back it leads to falling like a tree, in an equally unnatural way. In fairness, Luis Suarez was terrible for arching the back (and for pretend rolling around in agony, which was embarrassing), which was highlighted in England 10-20 years ago as a sign of cheating; but a lot of foreign players don’t get penalties for fouls, no matter how they crumble or how they try to stay on their feet. The data backs that up.

So, do English players “dive” or fall differently? My sense is that players like Harry Kane have mastered the plank-like flop (see the image to last week’s piece), where there’s such an attempt to not arch the back it leads to falling like a tree, in an equally unnatural way. In fairness, Luis Suarez was terrible for arching the back (and for pretend rolling around in agony, which was embarrassing), which was highlighted in England 10-20 years ago as a sign of cheating; but a lot of foreign players don’t get penalties for fouls, no matter how they crumble or how they try to stay on their feet. The data backs that up.