https://tomkinstimes.com/2021/03/a-damning-indictment-of-english-referees-regarding-foreign-players/

I have spent the past month working continually on a project to assess the fairness of referees, including various potential biases they may have, and which players and teams they seem to favour and which they seem to punish.

I am still unsure of when to publish the whole study, for which, with the help of various people, I’ve mined tons of data.

As well as with TTT’s regular writers (including Andrew Beasley), I have been working with a high-level graduate of Harvard and Oxford who works as a project leader at one of the world’s biggest businesses (TTT subscriber CVT123), as well as another academic currently at Oxford University, on the findings. (With erstwhile Tableau Zen Master Robert Radburn doing some data visuals, in addition to my more simple spreadsheet outputs.) Basically, it could now easily make for an academic study, and having been asked about considering that route, I’m currently pondering whether to take it to that level.

Having been driven to distraction by the officiating these past few seasons, and the apparently botched introduction of VAR (albeit some teething problems are to be expected), I wanted to actually find out if my frustrations were based on reality. I’m sure the same applies to the others who helped with this study. I’m sure we all have our own biases too, but the data has to be allowed to speak for itself. No subjective data was used. The only subjectivity was by the officials.

In the past month I’ve written several 5,000-word pieces that are still gathering metaphorical dust on my hard-drive because, as soon as I reach a conclusion, I think of other variables to check, and find more data to mine, or new ways to filter the data at my disposal. Sometimes it strengthens my hypothesis, and sometimes it weakens it. Either way, it’s like a rabbit hole of never-ending possibilities to check. (And I don’t want to spend the rest of my life sifting through it, lest the last of my sanity be drained away, along with my will to live.)

I want to get this right. I want to be fair to the referees, who have a very difficult job, but also point out the bad ones or their overall biases.

A lot of the preliminary findings are damning of Premier League officials, and show what appear to be strong biases, and in some cases, anti-biases, as they try and bend over backwards in certain situations to try to not look biased (which everyone has to do in modern society).

For instance, if Liverpool are officiated by a referee from the North-west then the Reds’ positive decisions diminish massively – but with one Mancunian referee (Anthony Taylor) more likely to give Liverpool positive decisions than the North-west refs who hail from closer to Merseyside.

Indeed, across a sample of 68 games since Klopp took charge, referees from the North-west absolutely hammer Liverpool on the whole, compared against all the other referees. (And by ‘hammer’, that is also compared to how those same referees officiate other big clubs.)

Similarly, age seems to play a big role in Liverpool’s case: older referees are also incredibly harsh on the Reds overall, with those born after the old myths about the Kop winning penalties and influencing refs less likely to show a desire to avoid all big decisions at Anfield. There’s a provable home/away difference in officiating across all clubs in the study, and other anomalies. But that’s all for another time.

(One thing that was clear from the data is that Liverpool have a ton of “absent penalties” compared to all their rivals since Jürgen Klopp arrived in 2015, even if Liverpool, in the first 12 years of the Premier League, won an excess of penalties – but that doesn’t help this manager, these owners, these players and the current fans who are paying emotionally and financially to follow their team. Referees clearly officiate Liverpool very differently from the other five major contenders I studied regarding the number of decisions they make, based on tons of data from every single game, and they almost go “on strike” at Anfield. But I’ll save that stuff for another time too.)

Going back a couple of years, I had already studied the 600+ penalties given in the Premier League between 2011 and 2019, and found disparities between the awards given at both ends to British players and overseas players, with the British less harshly treated based on the percentage of minutes played. For that old study, with help from volunteers, we simply listed the team, the player fouled, that player’s nationality, and then the name and nationality of the fouling player. Then, as with everything in this much more expanded study, I am not factoring in whether penalties and sendings off were “correct”.

This is purely based on big data, and the belief that biases will show up in the numbers.

(That said, we have prepared videos of some of the decisions affecting Liverpool in the last two seasons, although this is not a study skewed towards Liverpool in any way, albeit we will focusing on the results that affect the club we write about. We want to highlight some of these “absent penalties”.)

One thing I wanted to do this time was to expand on that 2019 work, and to split it down further, to see if English players benefited more than Scottish, Welsh and Irish players; to see if English referees benefited their “own” more readily, and also, to see if England internationals appeared to get extra preferential treatment. So, this was all underway – albeit I was drowning in data and in the challenge of turning it into comprehensible articles.

But today has seen a development. Ex-referee boss Keith Hackett has been talking about how Jürgen Klopp has to inform Mo Salah to stop diving – so I thought it was worth looking again at how foreign players are treated at both ends of the pitch, and leaving the rest of the officiating study (which teams win a greater or lesser number of big decisions than expected; which refs are kinder/harsher to certain teams, and the role age and birth location plays; and things like home vs away biases, etc.) to another time.

Indeed, Liverpool played for seasons with their front three of Roberto Firmino, Sadio Mané and Salah, and had Virgil van Dijk, Alisson and Joel Matip at the heart of the defence, they were primed to be hit hard by any potential anti-English bias from English refs. And with Jordan Henderson and James Milner as midfielders, the team’s “Britishness” was often confined to wider and more central midfield areas – although both Andy Robertson and Trent Alexander-Arnold got into the opposition box more than some attacking midfielders at other clubs.

Whilst I will – in one form or another – publish all the data for all the issues in the full study in due course, for now this is a very Liverpool specific piece on the issue that affects the club to an outsized degree. That said, it also affects the players of other clubs, too – and hopefully the study, as a whole, will prove informative to fans of all clubs and neutrals alike (and if any non-Liverpool fans want to do a similar study or to try and replicate our results, I’d encourage it).

Expected Penalties

First of all, TTT subscriber “CVT” created an expected penalties model based on the number of Penalty Box Touches (PBT) of the ten English players who win the most penalties*, to set that as a baseline against which similarly (if not additionally) talented foreign players could be judged, as well as everyone else. The r2 correlation was 0.92 (or 92%), with anything above 0.75 considered “substantial” (according to a quick google of interpreting the results).

*Four or more since the start of 2017/18, with all data on PBT collated from the superb https://fbref.com/en/

In other words, for these ten English players – henceforth known as The English Ten – the relationship between the number of touches in the opposition penalty area and the number of penalties won is very strong. Indeed, remove the outlier Jesse Lingard (not to be confused with The Outlaw Jesse James) and the r2 goes up to 0.982, or almost 100%. Give these players between 30-80 touches in opposition areas and they’ll get a penalty.

The English Ten are: Raheem Sterling, Wilfried Zaha*, Jamie Vardy, Callum Wilson, Marcus Rashford, Dominic Calvert-Lewin, Jesse Lingard, Danny Ings, Glenn Murray and James Maddison. (Harry Kane won a penalty the evening after we collated the data!) On average, they get a penalty every 73 PBT, with Lingard averaging one every 38 PBT.

*As with my 2019 study, I’ve counted Zaha as English, as he played 17 times for England age-group sides and twice for the full team, and has been in England since a young child. As such, I would expect referees to treat him as English, just as they would Raheem Sterling, who moved to England at a similar age, but who stayed with the English national team. (Which is not to diminish Zaha’s allegiance to Ivory Coast, but he was an England international first.)

So, based on this analysis, we can say that The English Ten win penalties at a fair rate (based on the correlation between touches and awards), albeit some are a bit below the line and some are above. The problem is, almost no one else wins penalties at that fair rate.

A lucky few overseas players do, but on the whole, they are much less likely to be given penalties, even though The English Ten are not exclusively brilliant attacking players. Several are (Sterling and Zaha, for instance); some are not. Glenn Murray was slow and big; Jesse Lingard is small and fast; Danny Ings is dedicated and more than decent, but not world-class by any measure. Whilst no one can live up to the high bar of “fairness”, it’s interesting to see the margins by which everyone else falls short.

The clear problem is that once you overlay all the foreign players to win four or more penalties since 2017 onto the same fairness line, they fall short. Timo Werner, the Teutonic attacker who is struggling for goals – but not in terms of winning penalties – is a clear exception. Paul Pogba also wins more than expected, whilst Anthony Martial is the only foreign player to win a lot of penalties (more than four) at the same rate as The English Ten, which we have decreed as the fair amount.

However. Add Mohamed Salah, Riyad Mahrez, Roberto Pereyra, Sadio Mané, Alexandre Lacazette and Richarlison, as the other overseas players to win more than four, and they slide to the “harshly treated” side of the graph like the capsizing Titanic. Indeed, I asked to have Roberto Firmino added to the graphic too, as the Premier League player to have won the fewest penalties based on his expected totals: one from 785 PBTs, which would lead to 10 penalties for certain English players, some of whom are far less skilful. (For someone who drops deep a lot, Firmino is also in the box a lot, too. He’s everywhere.)

Which means, Liverpool have three outliers, all harshly punished. Of course, some players haven’t even won a penalty, and Firmino aside, the qualifying limit was four.

You could add the Portuguese Diogo Jota, yet to win a penalty despite 401 touches in opposition penalty areas since his debut in the top-flight with Wolves (over 50 of them with the Reds), and Liverpool have a quartet who, since 2017, win a penalty once every 213 PBT, compared with 38 PBTs for Lingard, 52 for Glenn Murray, and 73 for The English Ten. And I would argue that Salah, Jota, Firmino and Mané are, on average, better than The English Ten, if not not necessarily better than every member of The English Ten (that is debatable). Indeed, I think we can “prove” that with data, as I will come on to.

Or maybe that quartet of Liverpool’s just aren’t very good, or quick, or skilful, right? Murray and Mané both have four Premier League penalties since 2017, but Mané needed four times as many touches to win them. Obviously that’s because Murray was the Lionel Messi of English football.

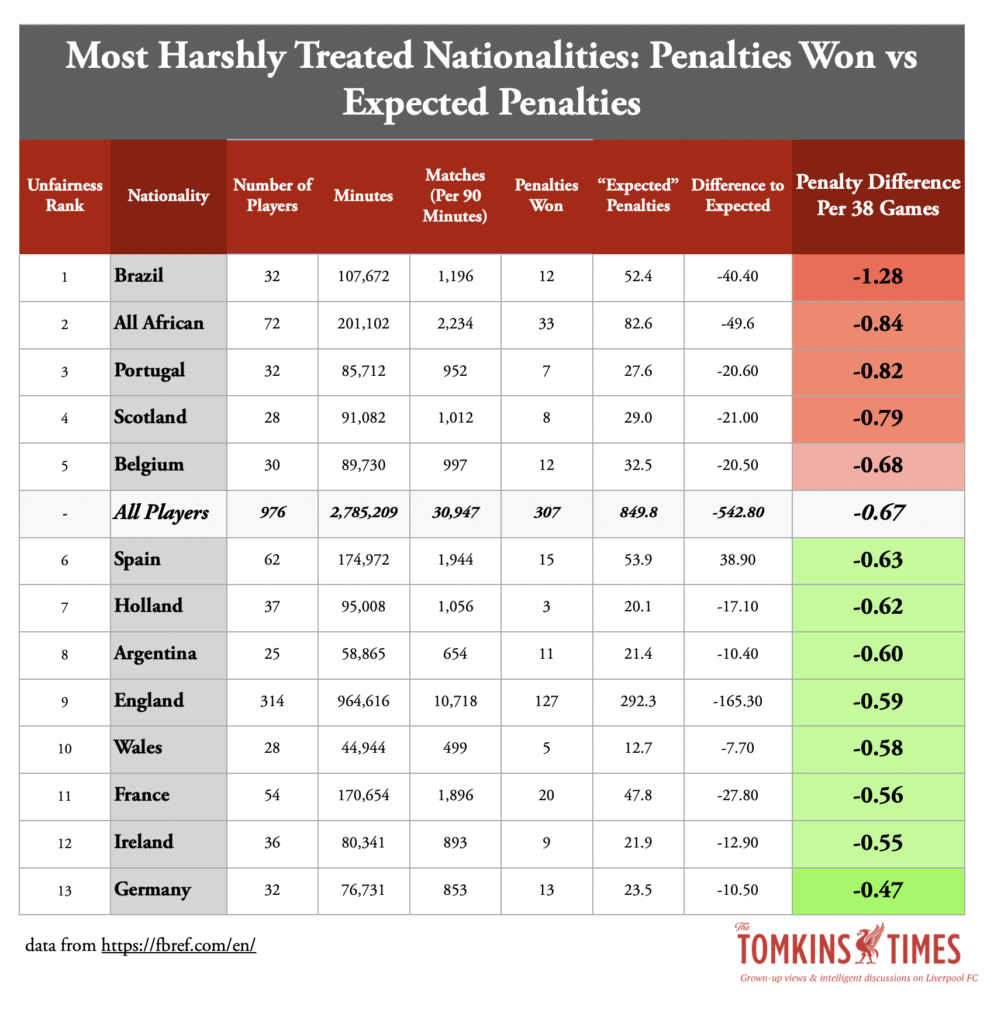

Brazilian Attackers Are Rubbish, Right?

Everyone knows that Brazilians can’t play football. And African attackers aren’t that good, either. Everyone knows that Jesse Lingard, Glenn Murray and James Maddison would all start for the Brazilian national side, even when at its best.

This is where it all gets worrying in the data. While I won’t step too far into the minefield issue of race (other than to say that English players of all races seem fairly evenly treated), there seems a strong xenophobic stench in the data from how refs treat players who did not grow up in England.

“Foreign-ness” seems more of an issue, given that plenty of non-white English players win a lot of penalties – although being foreign and darker-skinned may be even more of a punishment – but that’s for other people to decide. However, for the purposes of this study we have stuck to nationalities, which are more easily defined, rather than race, which, in contrast to place of birth and country represented, is not listed in major databases. For the record, due to their varied smaller sample sizes as individual countries, African players have been grouped together – which is not to say, in any way, that all Africans are the same, but they may be viewed as such by certain referees in terms of their “otherness”.

As an aside, I’ve previous shown when studying just Liverpool, that the Reds have won far more penalties since 2002 when the team has been full of British players, and that a British manager helps, too (albeit perhaps because they prefer British players). The only exception was Gérard Houllier’s side of 2002-2004, which had fallen dramatically from its exciting 2000-2002 heights, but still ranked 2nd and 3rd in the Premier League for penalties won in those two seasons, thanks to a heavily English team. Liverpool’s penalties last spiked in 2013/14, when seven of the 12 were won by fouls on British players (plus three on Luis Suarez, and two handballs where nationality was not taken into account), with British boss Brendan Rodgers in charge. In 12 seasons at the helm since 2002, no foreign Liverpool manager has seen his side finish as high in the penalty rankings as they have in the league table; whereas no British manager has finished lower. So this suspicion has been with me for years. The more I parse the data across the whole Premier League, the clearer it seems to become. (Indeed, the only noticeable change was in 2019/20, following my 2019 articles on the subject, before things returned to “normal” this season.)

The fact that Brazilians are three times less likely to win a penalty per 1,000 PBTs than a German, and 2.5 less likely than an Irishman, is worrying. African players are the next most harshly treated. (Good job Liverpool don’t have any Brazilian or African attackers, eh?)

English players need half the penalty box touches of Brazilians to win a penalty, while Africans need 50% more PBT than English players to get a spot-kick.

(Despite English and British players being booked far more frequently for diving than Brazilian or African players. I found this date: 2015-2019 yellow cards for simulation: 4 – Wilfried Zaha; 3 – Dele Alli, James McArthur; 2 Sadio Mané, Raheem Sterling, Pedro, Adam Smith, Leroy Sané, Joshua King, Martin Olsson, Roberto Pereyra, Pierre-Emile Højbjerg, Shkodran Mustafi, Daniel James. In his time with Liverpool, Salah has been booked just once for diving.)

(For the record, these are the most harshly treated players in the opposition box from some of the main European nations, listed in order of the most-harshly treated per country. Germany: Leroy Sané, Ilkay Gundogan, Mesut Ozil, Shkodran Mustafi, Antonio Rudiger. Holland: Georginio Wijnaldum, Patrick van Aanholt, Virgil van Dijk, Anwar El Ghazi. Belgium: Eden Hazard, Christian Benteke, Romelu Lukaku. France: Alexandre Lacazette, Abdoulaye Doucoure, Olivier Giroud, N’Golo Kante, Lys Mousset.)

Dangerousness!

So, are English players just generally more dangerous than Brazilians or Africans? It seems unlikely, given that only the exceptional foreign players (full internationals, especially those from outside the EU prior to 2021, who get special exceptional-talent-based visas) could join our league, but any number of mediocre English players can – and do – ply their trade here.

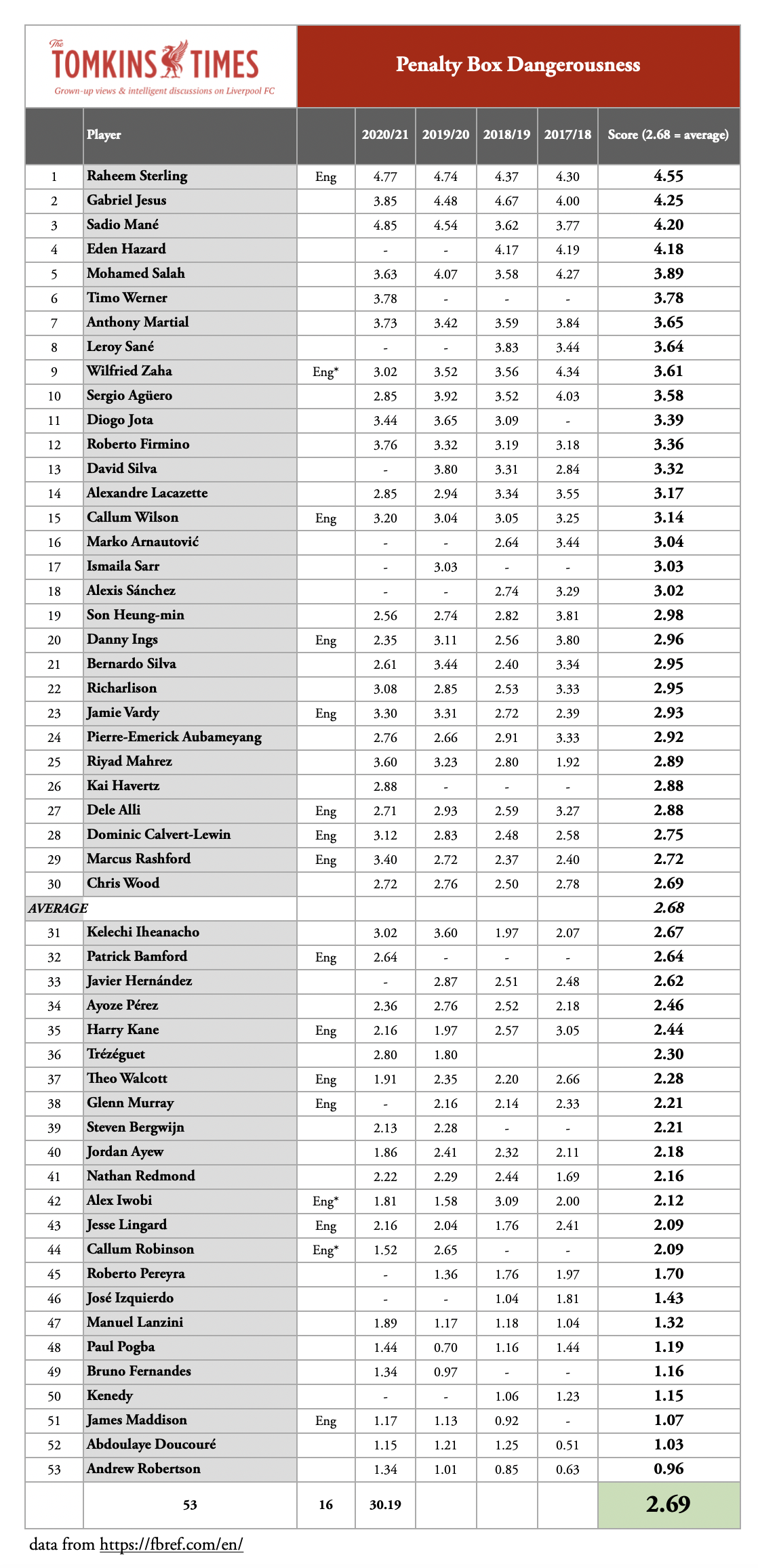

With this in mind, I worked with Andrew Beasley, again using the data from https://fbref.com/en/, to go beyond what I will call “standard” PBT (the gross number of touches), to delve into “dangerousness”. As detailed in more length for TTT subscribers last week, we selected six metrics to try and hone the PBT data into something that distinguished penalty-box loiterers with genuinely dangerous players. The six metrics we chose were as follows:

– Carries Into The Penalty Area (Per 90)

– Successful Dribbles (Per 90)

– Penalty Box Touches (Per 90)

– Progressive Passes Received (Per 90)

– Average Shot Distance

– Non-Penalty xG Per Shot (average)

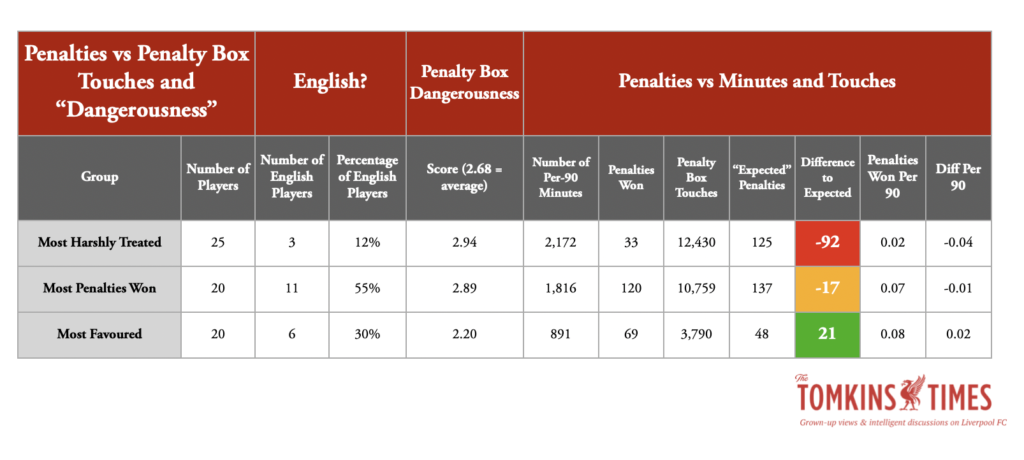

We then applied them to a group of 53 players, who comprised the 20 who won the most penalties, the 25 who had the greatest shortfall in number of penalties (absent penalties) and the 25 who had the most “unexpected” penalties (i.e. more than their expected totals). As you can see, this meant a number of players appeared in two of the three datasets (for example, Mo Salah wins a high number of penalties, but also, has a high number of absent penalties), which took it from 70 down to 53.

We ranked all the players on these six metrics, and anyone who had the top score was assigned 1.0, and anyone who had only half the number in that metric would be 0.50, and so on; and these were averaged out over four seasons. A maximum score across all six metrics would be 6.0, but no one average above 5.0, which would surely be Messi-esque.

Do the six metrics capture everything? No. But they cover dribbling success rate and carrying the ball into the box; touching the ball in the box (can you not win penalties just by controlling the ball with your back to goal, or receiving a pass?) and in dangerous positions; and the closeness to goal for their shots and the clear-cut chances are covered by that and also xG.

The top player for dangerousness? Raheem Sterling, who is also the top penalty winner. (That said, as explained last week, the top individual score in any season was Sadio Mané’s for 2020/21 so far, at 4.85.) Sterling averages 4.55.

Overall, Sadio Mané ranked 3rd (his last three seasons have seen a big incremental jump in dangerousness), Mo Salah 5th, Diogo Jota 11th and Roberto Firmino 12th. Only two of the top 14 were English.

Logically, all of these players should have vaguely similar penalty awards based on their minutes played and their involvement in the box. But it varies greatly. Sterling has 13, Gabriel Jesus none; Zaha has 10, Firmino one.

We found that, on average, the group of 20 players who had won the most penalties were very dangerous indeed; but not quite as dangerous as the 25 players who seemed strangely harshly treated when looking purely at the number (and not the specifics) of their penalty-box touches – including the Brazilians and the Africans.

Add the specifics of their PBTs – the dangerousness – and they become even more harshly treated. They are almost exclusively foreign players, too. Only 12% are English, compared to the 55% for those who win the most penalties, and 30% of the group that win the greatest number beyond what is expected.

By contrast, that most strangely favoured group – 30% English – were by far the least dangerous when looking at their general stats, too. On average, non-dangerous English players win far more penalties than dangerous foreign players.

Only three of the most-dangerous 19 players were English (and four of the top-ranked 22), although this was a group of 53 selected for the aforementioned criteria (most penalties won, and a big positive or negative swing in the number of expected penalties based on standard penalty-box touches), and does not include players like Jack Grealish, Phil Foden and Michail Antonio, whose 2020/21 averages would put them into the top 20 (but equally, so would those of some overseas players not included; and the pre-2020/21 averages of Grealish, Foden, et al, would take them out of the top 20).

Of course, Grealish and Antonio have won penalties (plural) in the four seasons covered. Harry Kane rates very low on dangerousness, which was a bit of a surprise – but he does seem to play deeper these days, and he was in the box a lot more prior to the start of 2019/20 according to his dangerousness score.

Some of the 53 players are midfielders, and it’s hard to know why, given that they make far fewer entries into the penalty box, they can lead to winning a greater number of penalties than more talented strikers who spend more time in the box, and also make more entries into the box.

Overall, the main difference seemed to be whether or not they were English, and not their “dangerousness”.

As “CVT” put it based on standard penalty box touches: “Another simple way to say it is ‘if the Premier League players were given penalties at the same rate as the English Ten (Sterling, Zaha, Murray, Lingard, et al), then foreign players would get 177% more penalties’.”

Some of the English players play for more counterattacking sides, but a penalty should be a penalty whether it’s in a crowded area or on the break, if it’s a foul.

The latter may be easier to spot, with less going on, but it’s not like Sterling and Marcus Rashford haven’t won penalties on the break, or that players like Firmino, Jesus, Mané, Salah and Eden Hazard never counterattacked. So I’m not sure that argument stacks up.

If, visually, it looks more like a penalty on a counterattack than in a crowded area (where the ref’s view may be more likely to be obscured), then it’s up to VAR to correct for that. Equally, a counterattack will more often mean a referee is far further away from the action, and so is guessing a lot more – and hence, the bias comes into play. Again, VAR should correct for that.

Indeed, I’m not convinced referees can tell even 30% of the time if something was a foul, given the speed and the angles, and hence why I was in favour of VAR; but VAR has been used to back up bad decisions, and the same biases apply as they are the same group of referees operating the technology at Stockley Park. (Even Michael Oliver – generally the best ref – said that none of the Liverpool players appealed for the red card after Jordan Pickford’s foul on Virgil van Dijk, and now whenever I watch games I try to see which team appeals first and hardest for decisions, and how it seems to lead to them getting a lot of incorrect decisions. Much of a fast-flowing game of football is an optical illusion, depending on the angle viewed from.)

Equally, Manchester United seem to be favoured at both ends, but having an English centre-back (just one penalty conceded in four seasons, despite several good shouts against him), and several attacking English players, it could be more to do with that pro-English bias than anything more pro-United from referees (although the North-west refs do give United a lot more than they give Liverpool, and as reasonably generous as Mancunian Anthony Taylor is to Liverpool, he’s far more generous to United; while Mike Dean, by contrast, is also more generous to United than to Liverpool – who are the team he punishes the most, albeit from a smaller sample size).

So, do English players “dive” or fall differently? My sense is that players like Harry Kane have mastered the plank-like flop (see the image to last week’s piece), where there’s such an attempt to not arch the back it leads to falling like a tree, in an equally unnatural way. In fairness, Luis Suarez was terrible for arching the back (and for pretend rolling around in agony, which was embarrassing), which was highlighted in England 10-20 years ago as a sign of cheating; but a lot of foreign players don’t get penalties for fouls, no matter how they crumble or how they try to stay on their feet. The data backs that up.

So, do English players “dive” or fall differently? My sense is that players like Harry Kane have mastered the plank-like flop (see the image to last week’s piece), where there’s such an attempt to not arch the back it leads to falling like a tree, in an equally unnatural way. In fairness, Luis Suarez was terrible for arching the back (and for pretend rolling around in agony, which was embarrassing), which was highlighted in England 10-20 years ago as a sign of cheating; but a lot of foreign players don’t get penalties for fouls, no matter how they crumble or how they try to stay on their feet. The data backs that up.

This has been on my mind for decades. One of my first games as a semi-pro as a striker in the 1990s was an FA Cup qualifying round, and as a 5’10” forward with pace (but 11 stone) I found myself constantly having my shirt and shorts pulled by a 6’3” 15-stone 1980s-era Steve Foster lookalike, whenever I got in behind him. I’ve described it before as like trying to drag a tractor. He would slow me down, then, when my legs ran out of power from trying to shake loose of this great lummox, take the ball from me. I got nothing from the ref, and it happened all game. These days, in the same situations, strikers correctly stop, or “fall”, to draw attention to the foul; Adam Lallana did this against Everton in the cup a couple of years back, to win a penalty.

This is legitimate, and a world away from there being no contact and a pre-planned intent to dive. Even a hand on the shoulder can take away your split-second advantage, if you are a fast player; and a hand on the shoulder, just like two hands in the back or having hold of the shirt or the shorts, has never been legal in football. Shoulder to shoulder contact is allowed, but you cannot pull at an opponent.

In three recent games, Sadio Mané has been praised – but also called naive – for not going down when fouled in the box. But if he ever does go down, he usually gets nothing, and is accused of going down too easily. Indeed, the worst thing that most TV commentators say about their fellow Englishmen is that they went down a bit easily, even if it was a blatant dive. They are called “clever” or “cute”, while the foreigners are frequently labelled as “cheats”. Mané and Salah are frequently accused of diving, even when fouled.

Defending

It also works against foreign players at the other end. Fifteen non-English outfield players have conceded three or more Premier League penalties since the start of 2017/18, but just five England players have; and just two England internationals (Eric Dier and Kyle Walker).

While there have been more foreign players than English players in the league in that time, English players, if playing c.33% of the minutes, are likely to win 45% of the penalties, while foreign players, playing c.55% of the minutes (the rest being Scots, Welsh, etc.) are likely to win just 45% of the penalties, yet concede up to 70%. (Note: I calculated this data at a different time to the other data quoted, and this was using penalty data from www.transfermarkt.com and WhoScored for Opta data on minutes played and nationalities, with all English-raised players counted as English if they played for England youth teams, even if they later switched allegiances.)

England internationals seem greatly favoured by referees, too. While they are clearly better players than English non-internationals, they concede far fewer penalties than expected and win even more penalties than expected, when compared against often better foreign players (as well as the inferior uncapped English ones, which admittedly makes sense). Again, this needs to be investigated. No one has a right to an identical number of penalties, but big disparities in how referees treat players is a serious problem for the integrity of the league, even if these refs are not consciously penalising “foreigners”. (Their perception of who “dives” is also likely to be influenced by the narrative, awash in football during my formative years, that ‘only foreigners dive’.)

All foreign players – elite internationals in many cases – win and concede penalties at a similar rate to mere journeyman English players; indeed, overseas players concede 11.9 penalties per 1,000 games (so over a very long career, each could expect to concede almost 12), whereas for England internationals it’s 8.9 and for English non-capped players it’s 11.1. The likes of Virgil van Dijk (three penalties conceded in the past four years) are more punished than the likes of Craig Dawson (one conceded, in 6,000+ minutes, or roughly two-thirds of the playing time of the Dutchman).

England internationals also would win 19.8 penalties in a career of 1,000 games, but foreign ones in the Premier League would win 8.9 per 1,000 games, and uncapped English players 6.5.

The End is Nigh

There’s lot more to explore and reveal from the data, but I’ll go away and think about how best to share it. For now, I’ll share this article, and then go and do more work refining the data – but after a sufficient break to clear my head and breathe some fresh air.

But I’ll leave you with this quick snippet:

Combined Premier League penalties won by the following, 2017 onwards: Andrew Robertson, Georginio Wijnaldum, Trent Alexander-Arnold, Virgil van Dijk, James Milner, Xherdan Shaqiri, Jordan Henderson, Naby Keita, Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain, Joel Matip, Diogo Jota, Philippe Coutinho, Daniel Sturridge, Curtis Jones, Joe Gomez and Thiago Alcantara.

ZERO.

(Jota includes two seasons for Wolves)

From a total of 1,692 touches in the opposition penalty area.

… Glenn Murray. 210 touches in opposition area, four penalties!

… Jesse Lingard. 229 touches in opposition area, six penalties!