By Paul Tomkins.

Liverpool now have the right tools for success: a good scouting and analytics set-up (if used correctly – more on that later) and a world-class manager. And while the club still lacks the financial might of its rivals, it now has an exciting level of ambition, and the optimism to back it up.

PART ONE

Belief is crucial in sport. Anything that can give your team belief is important. Other skills are essential too, but they are nothing without belief. Knowing you can do this is vital, not least when the going gets tough and doubts start to appear.

So much of the game is in the mind, and it’s a balance between believing you can succeed and wanting to succeed. One without the other is a problem, as seen with Chelsea this season – they knew they could be champions, but having gorged like gout-ridden Georgians on champions pie, they weren’t as bothered anymore. (Or maybe they didn’t believe that they could retain the title, which is harder; or that it wasn’t worth the extra effort.)

At the bare minimum, your team should ‘want it’. I find analysis that “we just wanted it more than them” shallow, and yet at times it’s true. But if someone wants it as much as you, then you need to be better technically and tactically. At the very least, you should never want it less than the opposition.

You’ll have off days, of course, but looking interested should be the least fans can expect from their team. (Although a nervous team can sometimes go into its shell, especially if the crowd is flat or antagonistic – and look like they’re not trying.)

And as well as wanting it, at the very least you need to be able to do the basics, and have smart tactical plans.

While everyone talks of Luis Suarez, I still believe that Dr Steve Peters played a key role in 2013/14; one of Brendan Rodgers finest appointments. (In fairness, it’s not a long list.) While it’s hard to state what exactly Peters did, plenty of top athletes swore by his methods. He was associated with Olympic gold medals. For me, this is one of the areas where the manager thought outside the box. And to beat par, that’s essential.

The manager himself had proved little in the game beyond mid-table Premier League overachievement with Swansea – which showed real talent, but not the type of success that was relevant to Liverpool – so he had to foster a sense of belief from somewhere.

Let’s face it, not one player saw Rodgers turn up and Melwood and thought “this is the guy to lead us to the great things!” Not one player looked at Colin Pascoe and Mike Marsh and thought “these guys have been there and done it as coaches, I can’t wait to run through brick walls for them”. Rodgers arrived as a talented coach, but he lacked gravitas. He lacked trophies, Champions League experience. So it needed something extra; something to instil belief. He handled most of the players well, but Peters gave him a way to drive them on. Even if it was a placebo, placebos can be powerful.

The problem was that when that season ended in ‘failure’, Peters presumably couldn’t cajole a demoralised bunch of men, with Rodgers amongst their number. Liverpool had fallen off Everest just metres from the summit (which made a change after years of barely making it past basecamp; indeed, some seasons they seem to fall off basecamp). But getting so close, and then losing the main component of the side – Luis Suarez – killed belief.

From that moment on there was a sense of “the chance has gone”. And while Rodgers had briefly, but massively overachieved to get the Reds as close as he did, the fact that the defence was blamed for falling short, and the highlighting of lack of a Plan B against Chelsea, may have altered his thinking and clouded his mind. On top of this, the captain and club legend, Steven Gerrard, was a beaten man. The disappointment cut through everyone. Last season was grim.

The belief had evaporated, and after a brief winning start to this season, two heavy defeats – particularly the 0-3 against West Ham – shattered the idea (which I’d clung to) that a few new players and a few new coaches could reverse the spiral in mood. Rodgers had no credit left in the bank on which to draw. Once his team were limply beaten at Old Trafford, the writing was on the wall.

By contrast, Jürgen Klopp doesn’t need sports psychiatrists – although if he wants to use them, that’s all well and good (Liverpool need to utilise anything that can help). Like most fans, I’d have taken Klopp in a heartbeat in the summer, but it didn’t seem like he was within reach.

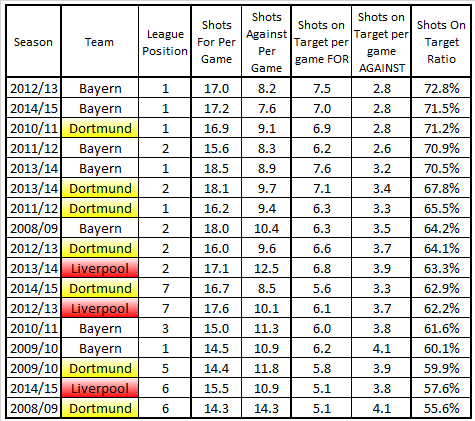

Klopp exceeded par consistently in Germany, although like Diego Simeone at Atletico Madrid, his side were soon one the top three richest clubs in their country, and up against only one super-club (two in Spain), and therefore it was easier to finish in the top four, and slightly easier to win the title. All the same, Dortmund, like Atletico, still massively overachieved, and not just for a season. When people gave these examples to me, I always thought that such coaches were as far out of reach as players like Messi and Ronaldo. These were exceptional; and therefore exceptions to the rule.

But here he is, Jürgen Klopp. Rodgers – a fine coach who will bounce back somewhere slightly lower down the league (and maybe back towards the top a bit later in his career) – has been replaced by a great one.

Just by his mere presence, Klopp has got the club, the city and the worldwide fanbasebuzzing. And no matter what arguments you could form for or against Brendan Rodgers, you’d struggle to find a single fan in any part of the world who would take him back at the expense of Klopp. His sacking – which I wasn’t 100% sure about, but teetering towards as the season wore on – suddenly seems essential when put into this context. It was a no-brainer.

Klopp comes armed to the teeth with achievement; the kind Liverpool’s players will respect. He climbed Everest with Dortmund – and to the very summit, planting a giant yellow and black flag. Then the next season he bloody-well went and did it again! – with the domestic cup as well. All this with a club that was lingering mid-table when he pitched up, and in financial crisis.

The year after that double – 2013 – he almost went one better, in the Champions League Final.

It’s a different challenge here, with a greater number of powerful rivals. To exceed “par” over a number of seasons is tough. But Rodgers had stopped looking capable of evenhitting par, after his one shot at greatness. Klopp’s Dortmund side also eventually failed, of course, but only after four or five seasons of pushing the boundaries of what was thought possible. He revived a whole club, before his high-octane project ran out of gas.

It’s dangerous to celebrate before the new boss has actually done anything in the job, but he is no nearly-man. Right now, even if getting our hopes up may lead to them later being dashed, we need to harness this incredible energy. Premature or not, people will be stitching new banners, painting new flags. Anfield will be (Kraut) rocking.

Who could fail to be inspired by Jürgen Klopp? If he can’t get your blood pumping then you better be checked for a pulse. Even the dead of Anfield, interred beneath the Kop-end goal, will be tempted to rise for this man.

Buy Smarter

Seeing as so much is being made of the transfer committee (and their laptops) this week, it’s important for me to show how, in my opinion, Rodgers’ fine coaching skills were undermined by his terrible record in the market. I hope to make this my last look at Rodgers’ own spending, but it seemed vital to quickly go over each and every buy, with no one-sided selections. (And once Klopp has taken charge of a game, we can start focusing solely on what he’s doing.)

With better players – as seen in 2013/14, when none of his own players were key components – Rodgers could make things happen. Even with the dodgy defending I’d give him 10/10 for that season. But as far as I’m concerned, his influence on transfers is what made Liverpool start punching below their weight.

James Pearce of the Liverpool Echo was one of Brendan Rodgers’ most vocal supporters, to the point where he was sent snarky messages of sympathy upon the manager’s sacking. So he’s unlikely to be negatively biased against him. (And I also hope that I’ve been a fair judge of Rodgers’ tenure, with no axe to grind, even if my opinion has vacillated.) In the week, Football365 asked Pearce who Rodgers wanted and who was foist on him by the committee. (This was in response to the revelations about Liverpool’sMichael Edwards not only having a laptop, but a nickname too.)

The list was more-or-less as I had expected, based on various media rumblings over the past few years. Whereas I’d tried to give each buy the benefit of the doubt at the time, it’s now time for a quick recap of what Liverpool got for their money, seeing as the media are taking fire at Liverpool’s analytics department.

Pearce said: “Rodgers was the driving force behind signing the likes of Fabio Borini, Joe Allen, Adam Lallana, Dejan Lovren, Rickie Lambert, Danny Ings, James Milner and Christian Benteke, while the other members of the committee championed the suitability of players such as Daniel Sturridge, Philippe Coutinho, Sakho, Emre Can, Moreno, Luis Alberto, Iago Aspas, Lazar Markovic, Divock Origi and Roberto Firmino.”

Which group of players would you want? Which group is “smart” and which group is, er, not so smart?

Rodgers’ list is exclusively Premier League-based, and largely dreadful. The committee’s list is mixed, but no more mixed than you’d expect from any sample of transfers. It’s notamazing, but it’s far from bad. For the purposes of this quick assessment I’ll use the emotive word ‘flop’, when it can also mean that they just haven’t succeeded (or had the chance to).

Fabio Borini (flop), Joe Allen (mixed), Adam Lallana (mixed), Dejan Lovren (flop), Rickie Lambert (flop), Danny Ings (very promising, but too soon to say), James Milner (worrying, but too soon to say) and Christian Benteke (promising, but too soon to say). You can add Kolo Toure (flop) and Mario Balotelli (flop), although the former was free and the latter was Rodgers taking a last-gasp gamble. What’s clear is that Borini, Allen, Lallana, Lovren and Benteke were all overpriced.

Buying proven Premier League talent is a myth, as I’ve been saying for a long time now. (Although I use a mainframe computer and not a laptop, and aside from bald dickhead I don’t have a nickname.) And not only are these players overpriced, and thus driving down the chance of finding extra value, they mean handing large fees to rival Premier League clubs. If Southampton have improved, it’s because Liverpool gave them sack-loads of money, which they reinvested wisely overseas by, er, using a large raft of analytics staff and not giving the manager all the buying power.

Liverpool’s committee buys? Daniel Sturridge (hit) – well, they’re already ahead. In terms of big successes, that’s already 1-0.

Philippe Coutinho (hit). 2-0. Back of the net. Game over.

And even the rest – beyond those two big hits – are probably better than Rodgers’ picks. Sakho (mixed), Emre Can (mixed), Moreno (mixed), Luis Alberto (flop), Iago Aspas (flop), Lazar Markovic (flop), Divock Origi (not yet given enough playing time) and Roberto Firmino (not yet given enough playing time). Simon Mignolet (mixed) is an obvious omission from Pearce’s list. Joe Gomez was also a committee recommendation, and one dating back 18 months, and he’s ‘promising, but too soon to say’.

You can add Tiago Ilori (flop), Oussama Assaidi (flop, albeit a profitable one). There were also a handful of unsuccessful loans, although it’s not quite clear who sanctioned those.

But to me, to focus on Assaidi at £2.4m, as the usually trustworthy Ian Herbert did in theIndependent, is a bit like saying Rafa Benítez cocked up his first summer’s buying by bringing in Antonio Nunez for £2m, and then ignoring Xabi Alonso and Luis Garcia. This kind of cherry-picking one mildly bad example and ignoring two outstanding examples that contradict it is very poor indeed. If Assaidi was a flop, where were Coutinho and Sturridge, signed the same season (once the committee was properly formed) to redress the balance? In that piece, nowhere to be found.

Rodgers is more-or-less quoted by Ian Herbert of thinking Sakho is “shaky” (Herbert told me on Twitter that he was merely “reporting” this), but that suggests confirmation bias on the ex-manager’s part; because if Sakho is shaky, Lovren – who wasn’t mentioned – is a bowl of jelly in an earthquake sliding down a sinkhole. Also, Sakho is younger. And Sakho was cheaper.

Markovic, Ilori, Origi, Can, Coutinho, Moreno and Alberto are all still aged between 20 and 23, and Firmino just turned 24. Joe Gomez is 18, and though clearly raw, already looks more assured than Lovren, at a fraction of the price. And while I think that having a team with a low average age (anything below 25) can be problematic, Jürgen Klopp fielded a team in the Champions League at a scarcely believable 22.9. He is not scared of fielding young sides.

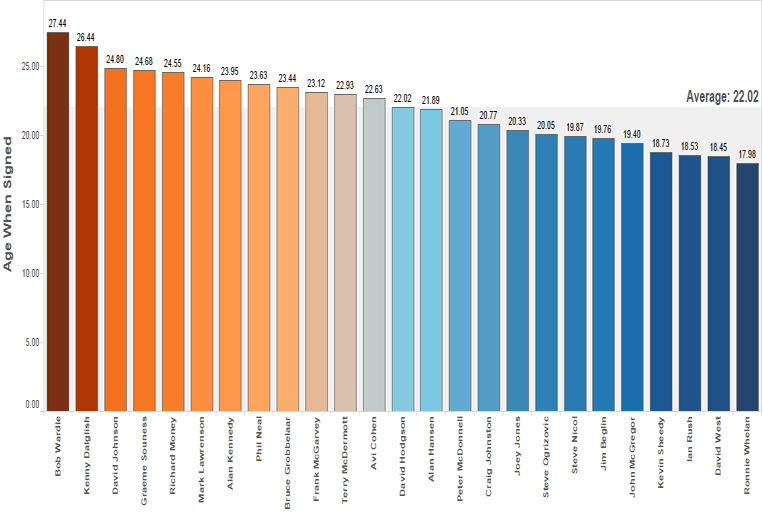

Klopp wants the first and last word on transfers, but not all the stuff that goes on in between. And the thing is, I’d trust his opinion on players, having worked with the best and frequently won games in the Champions League. And he has shown a willingness, with those he collaborated with at Dortmund, to buy from obscure markets: Robert Lewandowski cost £3m at the age of 22, from unfashionable Polish football. Liverpool can’t afford Lewandowski now, but they could have looked for someone comparable to where the Pole was at five years ago. Rodgers spent £3m on Rickie Lambert, if we’re going to make semi-random comparisons.

Shinji Kagawa arrived from Japan at the age of 21 for £300,000. Indeed, all Dortmund’s best buys were aged 20-24. Bender, Hummels and Gundogan were all just 20. Reus was 23, Mkhitaryan and Aubameyang 24 – underpriced homegrown talent and promising players from around the world. This approach fits with what the committee were trying to do. This wasn’t about filling the squad with ageing talent supposedly proven in theBundesliga.

Indeed, Klopp – with beautiful music to my ears – asked why should he go and buy expensive players from Dortmund when the whole world plays football? Rodgers greatest failing was the obsession with prior Premier League experience. Where was the point of difference? They often weren’t even the best Premier League players, and on occasions, not even close. Perhaps he didn’t trust the scouts and analytics guys and he wanted to only go for players he was familiar with. Well, that’s not good enough, on the evidence we’ve seen. If you want to go down that path, then you need the successes to back you up.

Going back to the opening point, someone like Rickie Lambert really wanted it, but his legs were going – Bob Paisley never bought an outfield player over the age of 26 in nine years, for this very reason (and the average age was 22). Paisley didn’t need a laptop to tell him that, and yet some people can’t see that this intuition and wisdom was part of ‘the Liverpool way’. Paisley bought young, and he bought from obscure sources; he didn’t buy ready-made top-division players.

Theoretically, any of Rodgers’ signings could still have worked out – they obviously weren’t hopeless or mediocre at their preview clubs. But none have. None. Zero. Nada. Zip. Some have had good spells, but it’s proved a terrible waste of money so far.

So this is where Liverpool fell below par, despite Rodgers’ talents as a coach. Had he stuck to what he’s good at, I believe things could have worked out better.

Of course, there are other ways to beat par, which Jürgen Klopp can definitely help with. It won’t be easy, or a “given”, but at last the club is thinking smarter and aiming higher.

PART TWO – FURTHER WAYS TO BEAT ‘PAR’

The second half of this article is for subscribers only.